Do you bite bullets? I pity the fool who doesn’t. Bullet biting is the mark of someone who’s smart and interesting. If you want to be a smart and interesting person, you should be biting bullets for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. If you’re of a certain persuasion — not that there’s anything wrong with that — you might enjoy biting bullets at brunch, too.

Bullet biting means accepting weird and counterintuitive conclusions that logically follow from the premises you endorse. It’s not always the right thing to do — sometimes, if you get a conclusion that’s really suspicious and you have a good reason to reject it, you should reject your premise or suspect there’s a flaw in your internal logic. But if you’re earnestly committed to a truth-seeking enterprise, you should be prepared to bite many bullets.

The most straightforward case for bullet biting, which has been voiced recently on Substack here, here, here, and here, is that most people have been wrong about most things for most of history, so it shouldn’t be surprising if most people’s intuitions are wrong about most things right now. Just because you think a conclusion is wrong or weird, that doesn’t necessarily mean you should reject it any more than someone in the 19th century should have rejected the principle of racial equality because it would have cut against the grain of contemporary moral fashions.

The best argument against bullet biting — some perverted form of which seems to be adopted here — is that our present institutions, including moral intuitions, are generally trustworthy because we’ve spent eons improving them through a process of trial and error, and any given revision is likely to be a regression to the mean. We’ve spent a long time developing genetics as a discipline, so if you concluded as a lay person that our current way of doing genetics is totally wrong, and you chose a random theory to replace it, odds are that things would go badly. So too with our moral intuitions! Unless you know why some Catholic weirdo put up a fence, you shouldn’t go tearing it down.

This response is confused, however. There is a difference between technical progress — an institution’s ability to do its job with increasing competence over time — and moral progress — or an increasing alignment between what its job is and what’s morally appropriate. In reality, our institutions are not selected for how good they are from the point of view of the universe, but how well they promote the values and interests of whatever class decides what institutions we have. We should therefore expect them to be increasingly good over time at executing their technical mission, but not necessarily that this mission should be a good thing. The institution of slavery became increasingly technically competent over the course of thousands of years, and by the 19th century, operated with remarkable efficiency. But that doesn’t mean slavery was a good thing!

Most institutions are like slavery in this respect. No matter how much moral progress we make, the institution-shaping class is almost certain to be committing countless atrocities and inappropriately excluding countless values and classes of beings — likely making up the vast majority of moral value in the universe — from the moral circle. Philosopher Evan Williams, author of the cult-famous ongoing moral catastrophe paper, argues that because there are so many ways we could be getting things catastrophically wrong, we should think we’re getting a very large number of things extremely horrifically wrong.

For a few purely illustrative examples of what an ongoing moral catastrophe might look like, consider our indifference toward the suffering of people very far away from us, our sleeping selves, factory-farmed animals and animals in the wild — especially fish and invertebrates — and people in the far future, as well as the disturbing possibility, raised by Williams, “that the function of the corpus callosum in a human brain is not to unite the two hemispheres in the production of a single consciousness, but rather to allow a dominant consciousness situated in one hemisphere to issue orders to, and receive information from, a subordinate consciousness situated in the other hemisphere.”

If any one of these is a legitimate cause for concern, then we’re currently perpetrating unfathomable moral atrocities. Conservatives say we should think our institutions are generally morally sound, or at least much better than if they were selected at random. But if we’re committing more moral atrocities right now than we could ever possibly think of, and our institutions fail to consider the vast majority of moral value in the universe, it seems that things would be better off if they were fundamentally different!

Since we can’t expect our intuitions to take into account the interests they don’t take into account, we shouldn’t consider it disqualifying if we think we have a good reason to take those interests seriously and it leads us to some conclusions we think are weird. We should, of course, pay mind to the Catholic weirdo and make sure the reason a value or class of beings is excluded is truly arbitrary, but if a good reason cannot be explicated that’s stronger than, say, “suffering is intrinsically bad and we ought to do something about it when the cost of doing something is minimal,” we shouldn’t hesitate before bullet biting. Refusing to bite the bullet in such cases would be like saying in 1800 that we can’t accept a principle of racial equality because we theretofore did not consider the interests of racial minorities. If the whole question at issue is whether you should consider the interests of racial minorities, it seems like the reason for saying no is merely because you disagree with it. (And why do you disagree with it? Well, because you disagree with it, of course!)

This was supposed to be the part of the essay where I make the jump from bullet biting to woke radicalism. Mere minutes before I was going to publish, however, a fellow bullet biter and friend of the blog

published an article smearing the good name of woke radicalism by associating it with the likes of “Antiracist Baby” author Ibram X. Kendi and Gaming Hall of Fame member Donald J. Trump. So let me take the opportunity to say in no uncertain terms: Kendi and Trump do not represent the good, hardworking extremists of the woke radical movement! More on that when you get to footnote 1.To bite bullets in order to expand the moral circle is to be a woke radical. Bentham has previously called himself a woke conservative, but this is a misnomer. Wokeness, in this context, refers to an awareness of injustice, including injustices against poor foreigners, sleeping persons, shrimp, insects, and other non-human animals, and people in the far future. Radicalism refers to an eagerness to fundamentally revise existing institutions and accept conclusions contrary to our intuitions. Wokeness entails radicalism because moral circle expansion requires revising our beliefs and the conclusions we draw from them. The more conservative you are, the less woke; the more woke, the more radical.

If you are deeply woke and you believe, as Bentham does, that insect welfare is the most important thing on Earth (personally, I think the most important thing on Earth is the girl reading this ❤️), then you should be appalled that none of our major institutions consider insect welfare so much as one iota. In fact, the methodical technical progress championed by conservatives makes insect welfare significantly worse by constantly giving us new and better ways to torture insects by raising them for food and feed.

If our institutions are almost ubiquitously indifferent toward the most important moral ends — or even actively misaligned, as in the case of animal agriculture — it seems that any random change to any random institution ought to be expected to have either negligible or significantly positive moral value, since it would either have no effect on the considerability of values or beings outside the moral circle, or else regress to the mean and expand the circle (since most moral value in the universe is currently outside of it). While it would be ideal to make sure we revise institutions in an optimal way, it is nevertheless likely that if you selected an element at random from the set “all possible ways to change society,” it would have positive expected moral value. Even if you think we live in a suspiciously convenient universe and most of our present institutions simply happen to be aligned with morally important ends — for example, that the growth of human civilization reduces the number of insects who live net negative lives — it would surely be better if the institutions were aligned intentionally rather than unintentionally.

The only exception to the principle that random revisions would be net positive in expectation are institutions that are already above replacement level, meaning a regression to the mean would only end up shrinking the moral circle. This describes only a tiny minority of institutions — since most institutions are wrong about the most important things — but includes those that directly perform a morally aligned function and those that help us identify where our intuitions go awry. The latter includes both direct knowledge-producing institutions — namely universities, especially moral philosophy departments and auxiliary fields — and the norms and institutions that enable them to succeed, like free speech and academic freedom. Since these institutions are already aligned to morally valuable ends, a woke radical should merely seek to promote technical progress within them rather than fundamentally revise their character.1

As for the vast majority of institutions that are below replacement level — where any random change would improve on the status quo — the task of the woke radical is complicated by the fact that we can’t actually think of random elements from the set of all possible ways to change society. If you don’t believe me, then go ahead: Try to think of a truly random revision to a given institution — let’s say the Department of the Interior. It should be random given the reference class of everything you either can or can’t think about the institution, and every way it either has or hasn’t been, or will or won’t be structured in the future. You have 60 seconds to come up with as many reforms as possible… go!

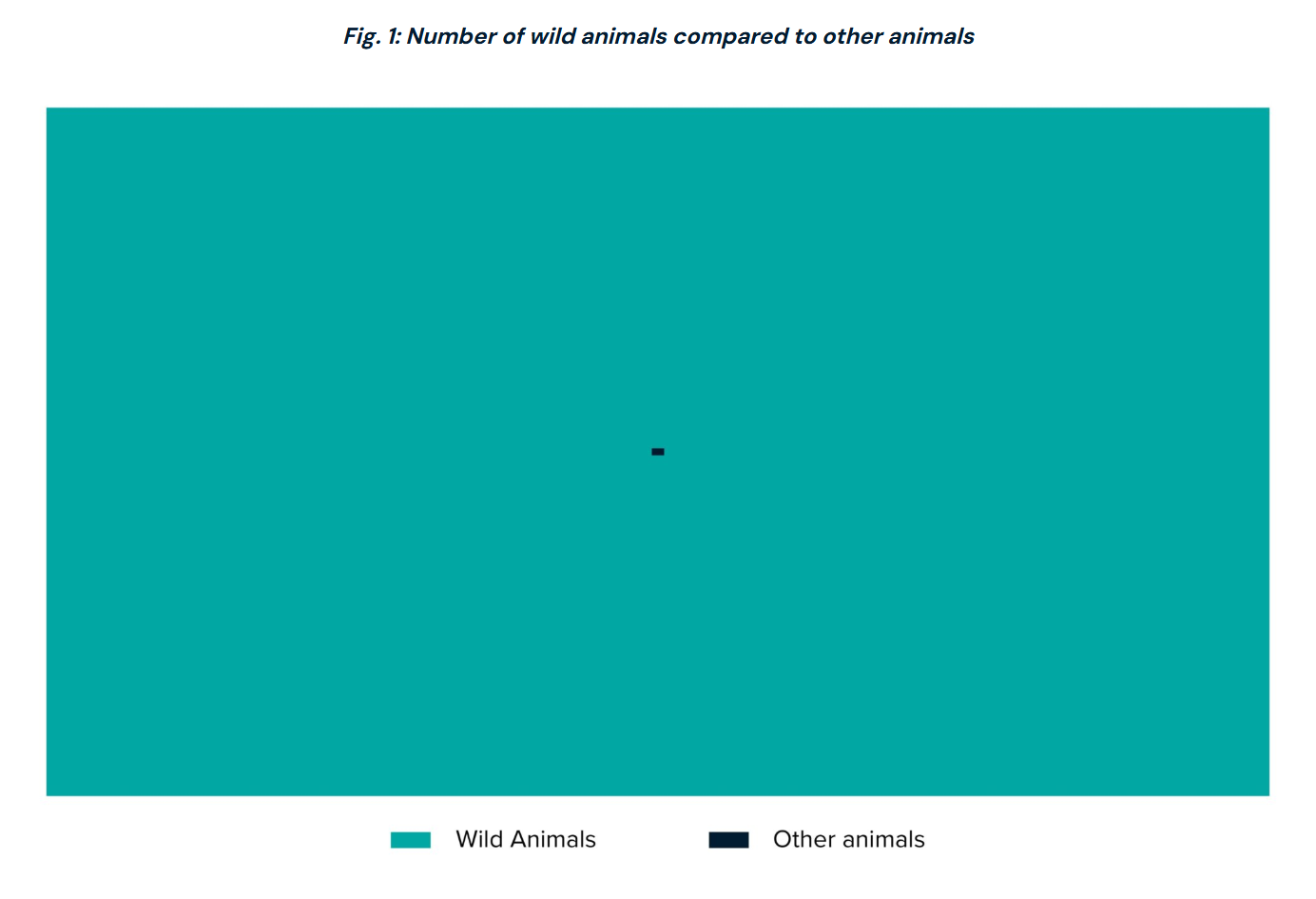

If you answered “yes” above, thank you for your participation. Now, please take a look at the list of reforms you came up with. How many of them have to do with wild animal welfare? If it’s less than 99.9%, you fail. If you only thought of things that have to do with wild animal welfare, you probably still fail because you didn’t think enough about insects. If you only thought about insects, how many other people do you think there are who only thought about insects?

Since we can’t truly implement random revisions to our institutions, we have to settle for the next best thing. If we can articulate a good reason for revision, and there’s no more compelling reason not to revise, we ought to do it no matter how weird it sounds — the Catholic weirdos be damned! No matter how technically competent our institutions are, the vast majority of them are misaligned with the vast majority of moral value. Woke radicalism is simply the observation that this is bad and the suggestion that bad things should be made good instead.

This is the essential difference between a woke radical like myself and a pseudo-woke radical like Kendi or Trump. The latter is not really woke in the sense that they care about injustice — they just care about power and self-righteousness. As a result, they seek to restrict the aligned functions of knowledge-producing institutions and undermine liberal norms like free speech and academic freedom, while attempting to bend the institutions to their will on issues of race (for the woke left) or nation (for the woke right). Observe that Trump went to war with Harvard to install loyalists in the academy and kick foreigners out of the country, not to establish a wild animal welfare program or make the dining halls vegan.

"personally, I think the most important thing on Earth is the girl reading this ❤️"

extremely axiologically implausible imo

I failed the exercise because I don't think, "Devote all DoI resources to drilling a big hole in the ground, and just keep drilling for as far as we can go," is related to insect welfare.