I Stand with Nicholas Decker

It's good to be smart and interesting.

I am an exponent of the peculiar belief that it is generally better to be smart and interesting than it is to be dumb and boring.

I know this is a peculiar belief because most of the smartest and most interesting people in the world are also the most controversial and despised. Any half-wit who knows what agreeable platitudes to spout can build an audience for himself and even occasionally come to be regarded as an intellectual. (Please ignore the following image — I don’t know how it got there!) But it takes a measure of wisdom and virtue to speak cogent truths to an unreceptive audience.

Paul Graham observes that every era has its own moral fashions. If you only believe the things you’re supposed to believe, it’s probably because you believe what you’re told. This is, of course, a good heuristic — no one can independently verify all of their beliefs — but the mark of a smart and interesting person is that they dissent from the moral fashion of the time when their reasoning and observational faculties suggest that they ought to do so.

It is virtuous to believe in shrimp welfare when nobody cares about shrimp. It is similarly virtuous to believe, as I do, that dream welfare matters, that we ought to spend a lot of money on fish contraception, and that we have good pro tanto reasons not to clean up the Hudson River.

It is even sometimes virtuous to believe — as opposed to “act on” — widely discredited and historically destructive ideas and ideologies, including Marxism-Leninism, racial supremacism, and the belief that

and even are anything but Very Failed Substackers — so long as you believe these things as part of an earnest and good-faith truth-seeking enterprise, and you would be dissuaded out of your beliefs by the proper evidence.One particular smart and interesting person I’m proud to call an acquaintance is the lowly second-year grad student and esteemed Substacker

of the blog Homo Economicus (one of only seven fine publications to be Officially Recommended™ by these United States of Exception). In addition to many dry posts about economics literature and Wikipedia editing, Decker is the author of several punchy, thought-provoking essays about niche and taboo topics. He has suggested, for example, that it’s wrong to have your own biological children if you could instead use the genetic material of someone whose children would have a better life —There are many people who they could be born to. Who would they pick? Do you have any right to deny them the father they would choose? It would be like kidnapping a child — an unutterably selfish act. You have a duty to your children — you must act in their best interest, not yours.

— and that there is a duty to commit immigration fraud by marrying a different non-citizen every two years in order to bring them to the United States and improve their standard of living1 —

If you are a citizen, you can essentially marry anyone, and they will be able to live in the United States. Once they have a ten year green card — or even while they have a two year, conditional green card — a divorce does not lead to them being expelled from the country. They are free to stay.

Isn’t it obvious, then, what we must do? The value of immigrating to the United States is very large, so large that I am not even going to bother quantifying it. I — you — we — can greatly help people. We can admit one person to the United States every two years.

Needless to say, being smart and interesting is a dangerous enterprise. When you’re not just being ignored, you constantly get lunatics in your mentions —

— and if you’re sufficiently smart and interesting, like Socrates or Galileo, the best you can hope for is to be remembered as a heretic and a martyr.

Earlier this week, Decker’s no-holds-barred pursuit of the truth finally caught up to him. After he posted a thoughtful, if intentionally provocative and undiplomatic, essay, “When Must We Kill Them?” — which appraises the ongoing collapse of the American constitutional order and raises the harrowing question in the title in reference to the Trump regime — Decker became the target of an onslaught the likes of which haven’t been seen since the heretofore record-shattering response to my article about Jeff Tiedrich last September.

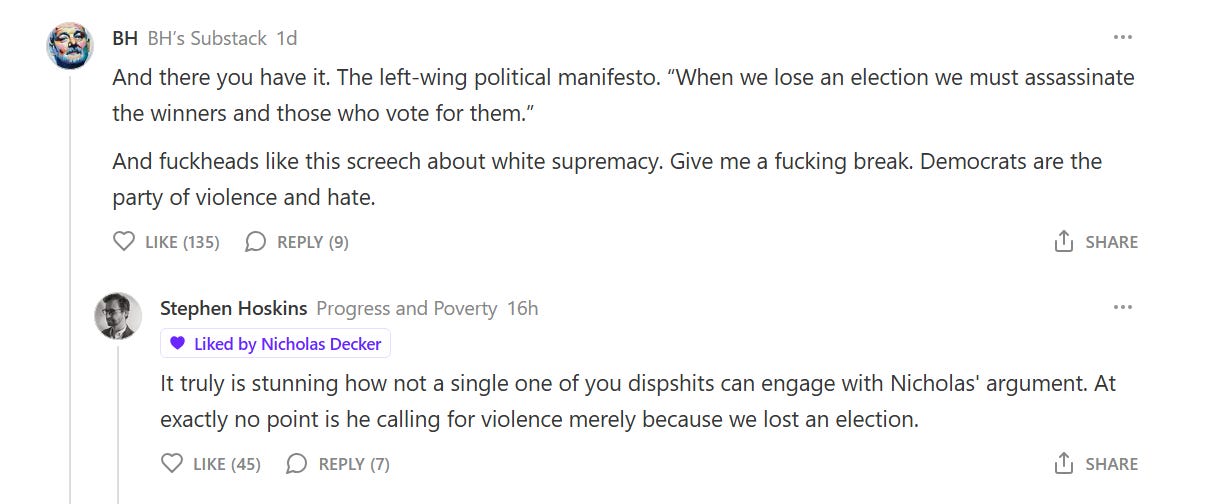

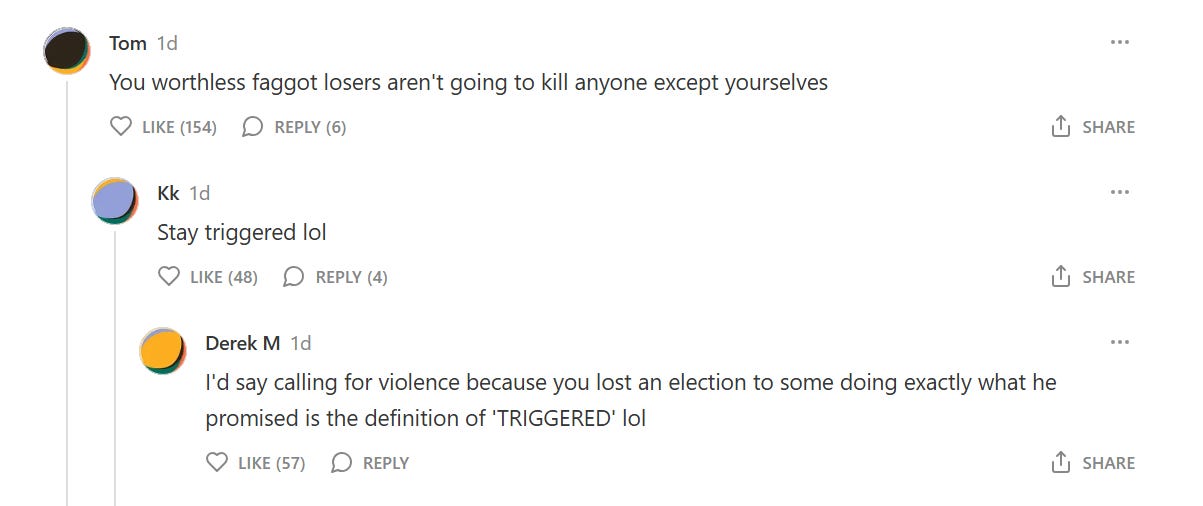

In addition to hundreds of angry replies on Substack — an astounding number of which seem to be inexplicably obsessed with gay sex — Decker received thousands of replies on Twitter, including one from a sitting U.S. Senator, outrageous coverage by a fair share of the lowest-IQ outlets in conservative media, and a condemnation from the official George Mason University Twitter account. Multiple conservative influencers have also called for him to be arrested.

Attempting to determine when it is appropriate to engage in political violence is, of course, a legitimate, legally protected — in fact, quintessentially American — and worthwhile endeavor. The United States was founded on the principle that if a government becomes tyrannical, “it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it,” including through revolutionary violence. As Thomas Jefferson famously wrote to William Stephens Smith, the son-in-law of John Adams, following the Shays Rebellion in 1787, Jefferson believed it was essential for citizens to instill the fear of God in government by conducting a violent rebellion at least once every 20 years, and thereby “refreshing [the tree of liberty] from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.”

Unless you accept unconditional pacifism — you agree with Gandhi, for an extreme example, that the victims of the Nazi Holocaust “should have offered themselves to the butcher’s knife” — then you must believe there is some point at which it becomes permissible to counteract the violence of the state with violence in kind. This is such an anodyne point that it’s not even considered controversial among most people to say you would have killed Adolf Hitler — you have to consider whether you would have killed Baby Hitler to make the question even minimally interesting. And still then, a sizeable plurality of people say they would have done it no questions asked.

Decker’s point is obviously not that the American left (of which he does not consider himself a member) ought to initiate politicide, but that we’re closer to the sort of King George III tyranny that justifies revolution according to the American founding tradition than we’ve been at any point in recent memory. He illustrates this cunningly — evidently too cunningly for his critics — by establishing a parallelism between the conduct of the second Trump regime and the conduct of George III as it’s indicted by the Declaration of Independence. Below is the relevant passage by Jefferson, with lines bolded where Decker draws an analogy to Trump:

The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences.

And here’s Decker — an astute reader might catch the similarities!

Evil has come to America. The present administration is engaged in barbarism; it has arbitrarily imprisoned its opponents, revoked the visas of thousands of students, imposed taxes upon us without our consent, and seeks to destroy the institutions which oppose it. Its leader has threatened those who produce unfavorable coverage, and suggested that their licenses be revoked. It has deprived us, in many cases, of trial by jury; it has subjected us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and has transported us beyond seas to be imprisoned for pretended offenses. It has scorned the orders of our courts, and threatens to alter fundamentally our form of government. It has pardoned its thugs, and extorted the lawyers who defended its opponents.

This alone doesn’t get you in trouble, of course. Unless you’re a partisan of the MAGA right, there’s nothing that contradicts the current moral fashion about identifying the tyrannical character of the Trump regime, or even comparing Trump to historical figures against whom it is widely accepted that revolutionary violence would have been justified. No more than a decade ago, even the mild-mannered, respectable, moderate conservative author and pop sociologist J.D. Vance was comparing Trump to Hitler!2

Decker only gets in trouble when he follows these widely accepted facts and values to their logical conclusion: that it is not unreasonable to believe that at some point in the near future, it will become justifiable to engage in revolutionary (or, more accurately, counter-revolutionary) violence against the principals and agents of the Trump regime, so long as this violence is not conducted glibly or indiscriminately. Admittedly, Decker could have made these qualifications clearer. But the point should not be lost on someone who reads the essay in good faith. Below is the section that’s triggered his critics and gotten him a visit from the Secret Service. Are you ready? Here it is:

If the present administration chooses this course, then the questions of the day can be settled not with legislation, but with blood and iron. In short, we must decide when we must kill them. None of us wish for war, but if the present administration wishes to destroy the nation I would accept war rather than see it perish. I hope that you would choose the same.

The rot of the present administration runs deeper than one man. The sacrifice of a hero is insufficient to save our nation, and a gust of wind on a summer day would not have saved us. For let us make no mistake; the problem is not one man, but a whole class of people. If one head is cut off, another would take its place.

The only part that’s concerning here is the last paragraph, and particularly the locution that the threat to the republic is posed not merely by the president, but by “a whole class of people.” Ideally, the task of identifying the members of this class would not be left up to the audience, few members of which are likely to be as thoughtful as Decker, or to have internalized the principle of distinction, or to be able to mute the part of their self-identity that’s tied up with the regime and sees a merely implicitly limited hypothetical call to violence against regime officials as an explicit and immediate call to violence against its supporters.

It is nevertheless clear to me, having either been a part of or adjacent to Decker’s intellectual milieu for my entire adult life, based on the homage to the American revolution and the repeated references to the “present administration,” that the class of people being identified as potentially legitimate targets for violence is narrowly limited to regime decisionmakers and the agents who would execute their illegal and revisionary orders. This is also clear in the following paragraph where Decker identifies the conditions he believes would justify a resort to violence:

And when is that time? Your threshold may differ from mine, but you must have one. If the present administration should cancel elections; if it should engage in fraud in the electoral process; if it should suppress the speech of its opponents, and jail its political adversaries; if it ignores the will of Congress; if it should directly spurn the orders of the court; all these are reasons for revolution. It may be best to stave off, and wait for elections to throw out this scourge; but if it should threaten the ability to remove it, we shall have no choice. We will have to do the right thing. We will have to prepare ourselves to die.

Yet his critics all insist he’s calling for the death of anyone on the right “because he lost an election,” even when it’s explained to them why this is false.

Why is this? The obvious explanation is that they disagree with Decker on the substance of what he thinks the Trump regime is guilty of. But that doesn’t tell you why they responded as caustically and obstinately as they did. I am a fan of the teen romance fantasy series Twilight, which I believe is better than Romeo & Juliet, but if someone wrote an article suggesting that it would be appropriate to use violence against Robert Pattinson in a hypothetical scenario where he imminently threatened to destroy the American constitutional order, I wouldn’t interpret it as a death threat against me.

A more reasonable explanation is that the people who don’t understand Decker’s article are simply dumb and boring people. Like everyone else, they believe what they’re told — or at least what they want to believe, and then what they’re told to believe in whatever echo chamber they happened to end up in. Unlike Decker and other smart and interesting people, however, they’re pathologically incapable of also thinking for themselves. It’s okay to think you should kill Baby Hitler. It’s okay to admire the American founders and their values. It’s okay to think we need a Second Amendment to deter state tyranny. Hell, for most of these people, it’s okay to think you should murder the vice president if you’re convinced he’s complicit in helping the other side steal an election.

Can you say the same thing about your own side? Of course not!

Why not? It doesn’t matter!

A smart and interesting person is someone who notices these inconsistencies and doesn’t simply paper them over. You don’t have to be precisely right about everything — you just have to make a well-reasoned, good-faith, unconventional argument and be willing to change your mind if someone gives you a good reason to do so. That might not seem like much of a challenge, but most people fail miserably. If telling inconvenient truths was popular, then it wouldn’t be very inconvenient, would it?

Being smart and interesting person often means having to deal with the mob. Most people would just give in; Nicholas Decker didn’t. Whenever you have a choice, don’t be like the mob — be like Nick.

At the risk of playing into the “Secretly Glenn Greenwald” allegations, if there are any Brazilian tops men between the ages of 18 and 34 who would like to take me up on this offer, you know where to reach me.

To be fair, Vance might still think Trump is Hitler — he probably just thinks that’s a good thing now.

Would it be a stretch to call Decker's article Federalist #86?

I think the reason many people took it as a threat is because they can see that Trump is getting closer to the threshold than any previous president has, and a lot of online Trump supporters openly want him to cross it and become a dictator. Is it Decker's fault that Trump has done multiple of the things the founding fathers pointed to as tyranny in the Declaration of Independence and that he constantly talks about wanting to do things that would be clearly dictatorial? If Trump supporters don't want people considering at what point revolution is justified, they should also be against fantasizing about doing things that would make revolution justified. As it stands now, they constantly indulge those fantasies, rightly making others worried that they will actually do them.