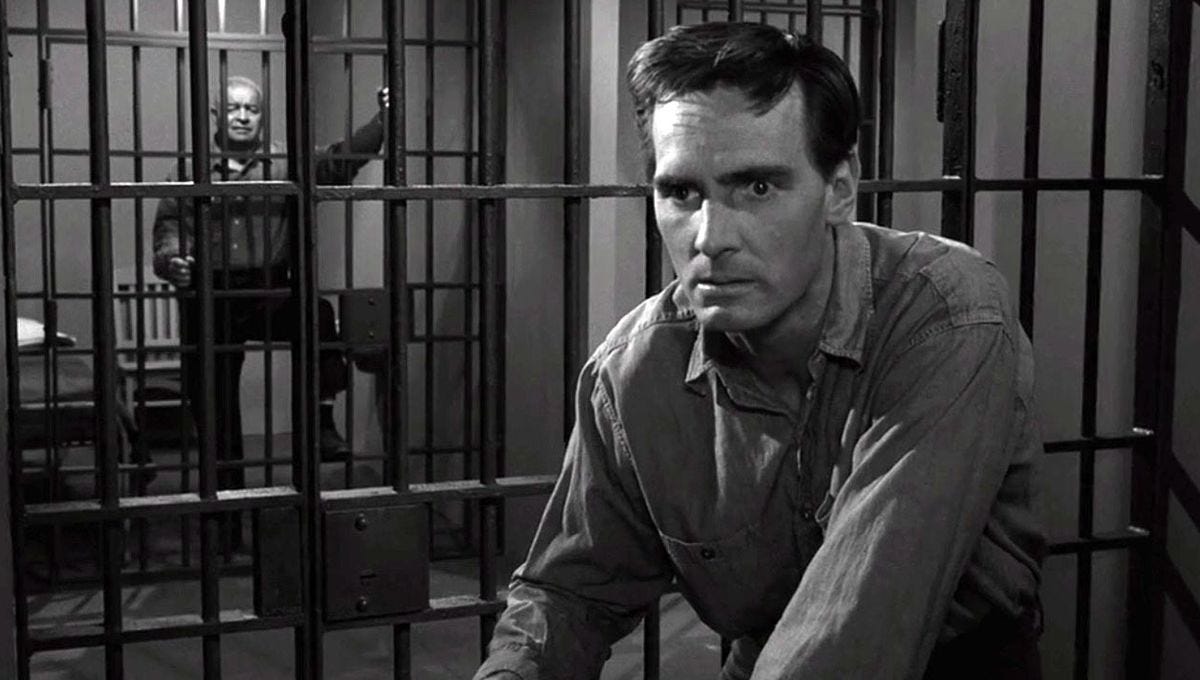

Last night, I watched an episode of the original Twilight Zone series, “Shadow Play,” from 1961. The protagonist, one Dennis Weaver, is trapped in a recurring nightmare in which he’s sentenced to be executed for murder. He pleads with officials to grant him a pardon, but it arrives a second too late. After he’s fried in the electric chair, the dream resets and he goes through it all again — then again, and again, and again.

In the universe of the episode, there are presumably two Dennis Weavers. The waking Weaver does not recall what happens to him while he sleeps, and the sleeping Weaver does not know anything outside the nightmare. If we could release the sleeping Weaver from his interminable torment, we would ought to do so, even if it would mean imposing trivial costs on him while he is awake.

That we should care about our experiences in an altered state of consciousness — even if we forget them when we return to normal — is such an anodyne point that it can be made clear to the most bumbling and dunderheaded audience known to man, namely the consumers of American screen culture.1 Apple TV’s Severance has recently brought the concept of split-mind ethics to the fore by imagining a world in which a working “innie” may be oppressed by his corporate Little Eichmanns while his civilian “outie” is unaware of his plight. Black Mirror’s “White Christmas” bravely asks: What if you could build a computer that tortures a miniature version of yourself? David Fincher’s Fight Club, meanwhile, gets the point across merely by relying on good old-fashioned mental illness.

These pieces of media are compelling precisely because we understand that something morally wrong is happening within their universe. We know intuitively that it is not right for a secondary or subordinate consciousness to suffer merely because it is considered secondary or subordinate. You should not torture your clone, your innie, your alter, or the protagonist of your dreams simply because you want to torture them — and to the greatest extent possible, you should try to improve their welfare when you can do so without incurring significant costs to yourself or others. This conclusion follows as long as you accept the basic value of beneficence.

Still, if you asked most people what they would do to better themselves while they dream, they’d probably just look at you like you’re crazy. Every night when we dream, we’re conscious for over half the time we sleep. We can fare better or worse while we’re asleep based on the things that happen to us in our dreams. There are proven ways to better remember and influence what happens in your dreams and therefore to improve your sleeping welfare at minimal cost to your waking self. Almost all of us fail to do these things, however. This is not because we have a good reason not to care about our dreams, but simply because, as Eric Schwitzgebel puts it, we don’t care about what happens to ourselves when we sleep.

But this is no good reason to ignore our own dream welfare. Once we’re awake, we may not care about what happened to ourselves while we dreamt. But we certainly did care while we were asleep. The fact that we are indifferent to our own well-being under certain circumstances should not be taken to mean anything more than the fact that we empathize less with suffering people who are far away from us than those who are close, or those who are outside our tribe rather than within it. The problem with Professor Schwitzgebel — and most of us — is that we simply aren’t woke enough.

There is just one major difference between dream welfare as it is represented in popular culture and dream welfare in reality. In the media, sympathetic dreamers have a strong sense of the future, or at least strong enough to complete a single story arc. In reality, dreamers are stuck in a perpetual present. Dreaming activates the parts of the brain responsible for short-term memory, which means we typically forget dreams within 30 seconds of having them.

But does this mean our dreams don’t matter?

Children typically don’t have retrievable episodic memories until they’re at least three years old. Do we think that young children’s experiences don’t matter? If you could stop a toddler from experiencing extreme mental anguish at little or no cost to yourself, would you do it? If you think the example is disanalogous because young childhood experiences have long-lasting effects on wellbeing, I invite you to consider the link between dream welfare and waking mood.

Or take something more pedestrian. Do you remember what you had for lunch two weeks ago? Hell, do you remember what you had for lunch two days ago? If you don’t remember, but you keep expending resources to have a lunch that’s better than the cheapest nutritionally acceptable lunch you could acquire, then your demonstrated preference is for the transitory hedonic value of lunch-having over whatever future goods you’re giving up by acquiring the lunch. As long as you continue to eat anything other than gray slop and vitamins every day, you should care about your dream welfare.

Don’t believe me? For every year since 2011, either The Big Bang Theory, Young Sheldon, or both has been a top-rated U.S. television program.

I am now woke on animal welfare, fish welfare, insect welfare, AI welfare, and dream welfare...where will the bloggers take me next?

I’ll try to learn to lucid dream this summer.

I’ve got an upcoming severance post in the same vein. I can’t believe I actually need to defend innie rights, but I have friends who are outie chauvinists.