Eighteen months ago, the plan was to get a Ph.D. in political science and research the distribution of power — a bit like Nuno Monteiro, a bit like Michael Beckley (even with similar analysis), only I would have better opinions and more heterodox normative commitments. At first, I pushed off applying for a year because I didn’t think I’d have enough time to prepare quality applications, and the one faculty member at my university who’s brutally honest enough to be trustworthy said it’s probably better to spend a year in the real world anyway. Then I pushed it off for another year because my undergrad thesis ended up being an intellectual history paper masquerading as political science and I started thinking about doing history instead. Then, I decided the whole enterprise is stupid and I got a job in government affairs.

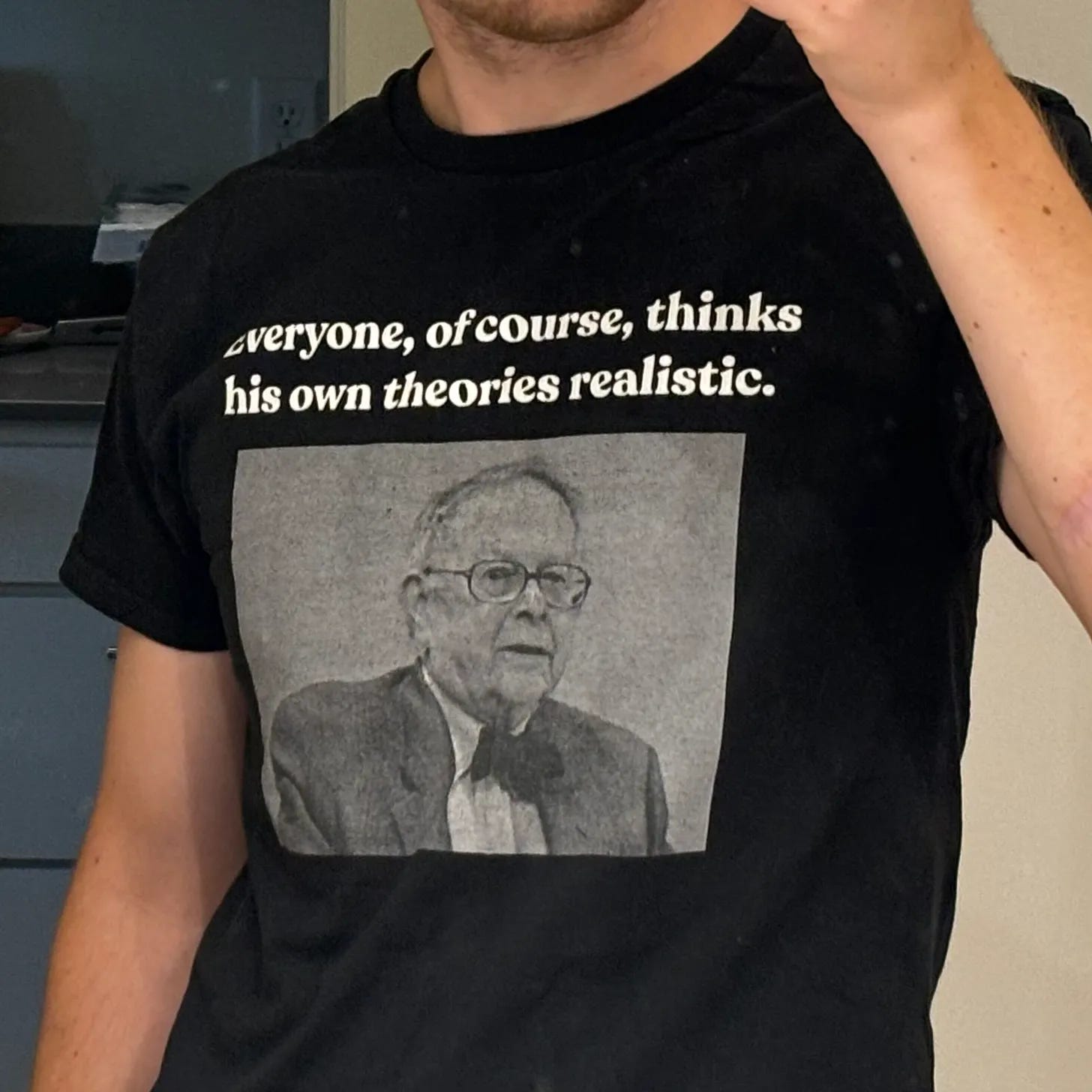

On paper, I’m probably one of the few people who should consider a Ph.D. in political science. I started reading scholarly journal articles for fun as soon as I figured out how to access them in my freshman year, I own N ≥ 1 signed print copies of journal articles and university press monographs on such topics as anti-statism during the Cold War, I have a shirt with Kenneth Waltz printed on it, and I bore people to death talking about the paradigms whenever they ask me about Ukraine and expect an update on current events. (Also, when people want to talk about the paradigms, I start telling them why I don’t like the paradigms.)

Like Bryan Caplan, I try not to follow the news because I understand there’s an opportunity cost and I’d rather read literature and get summaries of real-world events from Wikipedia. I consider myself statistically literate — though by no means adept — but International Relations is the second least quantified of the political science subfields (and let’s keep it that way!) and I’m competent enough with AI to get it to tell me what statistical methods I need to use and when I need to use them, and also to do all my coding for me. Besides, if worse comes to worst, I can just take a page from Lacan and Badiou and make shit up so people think I’m smart.

Still, I think it would be a bad decision for me to get a Ph.D. in political science. I’ve suggested the opposite in the past, but I think the analysis is flawed. If you want to become a public intellectual, the Matt Yglesias and Ezra Klein route seems a lot less circuitous than the Noam Chomsky, Bryan Caplan, or even Noah Smith or Richard Hanania route. At any rate, the fact that I’ve changed my mind ought to suggest that I’m making the case because I think the facts are really compelling, not because I have an emotional connection to one side or the other.

As I see it, there are basically no good reasons for anyone to become a political scientist right now, and very few good reasons for anyone to become any type of scientist, at least for the time being. We need a total and complete shutdown of academia until we can figure out what the hell is going on. And that means taking decisive action to prevent any more impressionable young minds from being sucked in by the allure of credentialism. Tanks in Harvard Yard? Well, maybe not Harvard College, but definitely the Kennedy School. I’m sure Larry Summers would love another 15 minutes of fame larping as the guy in the Tiananmen Square photo.

The biggest problem to me seems that we don’t even know if we’re going to need political scientists come a decade from now (if we even “need” them right now). I think we’ll get AGI sometime around 2030, which means that for anybody who’s not already in a doctoral program, it’s going to be obsolete by the time they finish.

A question that faculty ought to be asking: Why give out degrees that are immediately going to become useless?

A question that students ought to be asking: Why get a degree that’s immediately going to become useless?

I know we can’t be certain about these things, and stupid mistakes are really costly. But it sure seems like AGI is coming soon. And when it does, knowledge sector jobs aren’t going to be safe anymore. Sure, tenured faculty are probably going to be fine. They won’t be getting research grants like they used to, but the ideal-typical “research” will probably consist of some mix of prompt engineering, proofreading, and presenting at conferences. As for new hires, the academic job market is already hell. What happens when anybody with Deep Research can hit a button and generate a 50-page paper about why countries sometimes trade with the enemy during wartime? A job whose core functions involve person-to-person contact and wheeling and dealing is probably going to have a lot more security than one that involves knowledge production, at least until we get cheap humanoid robots.

It also seems that if you think there’s a good chance AGI is coming soon, you should spend the interim socking away as much money as you can to prepare for economy-wide structural unemployment and disturbingly plausible techno-feudalism. That means you probably shouldn’t sign up for a decade of poverty as a grad student and postdoc. Especially not when there’s an ongoing Yarvinist assault on the universities and a concerted national effort to defund research and dismantle scientific institutions.

Even if you think AGI isn’t coming, there’s already way too many people with a doctorate, at least in the humanities and most of the social sciences. According to a recent study of tenure track faculty members in political science:

The majority of PhD students, from 65% to 89% depending on the broad disciplinary category and 72% to 76% for political science specifically, enter their program with the goal of securing a [tenure track] academic position. Yet, there is a terrific imbalance between students’ desires and actual jobs that are available: depending on the discipline, only 3.5% to 20% of those who finish their program achieve this goal.

And unless you can get into a top program — which you probably can’t, or else it wouldn’t be a top program — your prospects are even poorer:

Six programs account for 33% of all faculty positions in PhD granting political science departments; 12 programs account for more than 50% of all positions; 27 programs (22%) account for 75% of all faculty positions; and 54 programs have fewer than five graduates in [tenure track] positions at a PhD-granting institution.

Then there are the pathologies of the academy. There are plenty of interesting, underexamined, and policy-relevant questions in political science, like theories of stereotyping in international politics — “and I mean theory here in the scientific sense, not that there aren’t enough articles about postcolonialism or the international as a Space of Queer Black Joy or whatever” — and state death. The advantage of the academy is supposed to be that you have virtually unlimited intellectual freedom. But that doesn’t mean you have an audience. You can write about these topics as a Substacker and get a fair reception, but if you’re an academic, no one’s going to care except the two or three people who have written about those topics in the past.

Thanks to modern communication technology, you can find an audience for almost anything as long as you’re smart enough. But the academy doesn’t reward work that’s substantively (and even often methodologically) interesting or important. It rewards work that mimics and fills in gaps in an already mind-numbingly boring literature. If you don’t want to spend your life running regressions to figure out how leaders with X qualities from Y regime type interact in Z international processes and institutions, you’re out of luck. Don’t you know the great debates are over?

So I guess this is all to say: If you want a job, and you want a job that’s not going to make you want to blow your brains out, don’t get a Ph.D. in political science. You can still do research — in fact, it’s going to be more accessible than ever if we get AGI. But you won’t be trapped in a dying and increasingly ossified profession.

Always enjoy reading you, but I feel somewhat obliged to comment given that I’m in a PhD program now! A couple of quick thoughts: what field do you imagine one might go into that will be safe? Granted, I can conceive of a future where we still work but it looks really different - like managers are largely just AI tamers and start-ups proliferate like crazy - but surely we should wonder when the human begins to just be adding noise there, too? I value my training now not because I want to be an academic (not what I’m optimizing for) but because being in my program actually does give me a lot of intellectual freedom and the ability to explore these sorts of things. That can be pretty hard to come by in most typical post-grad jobs. Like, yeah, if you think you’re going to be the last guy to get the tenure-track job you shouldn’t go for it, but equivalently, going for a consulting job that’s going to be obsolete in four years is probably not a great alternative either. In that light I do think an asterisked PhD kind of makes sense.

As a person with a masters in geosciences from about 20 years ago, followed by 20 years of consulting (mostly), I know there is a lot of truth to the old saying: there is more than one way to get a PhD.