What IR Theory Tells Us About Canada Becoming the 51st State

Why it's more likely than you might think.

At a press conference before the inauguration last month, Donald Trump was asked if he’s serious about annexing Canada, Greenland, and the Panama Canal, and doing it through military force. He responded that he’s open to invading Greenland and Panama, but he prefers “economic force” to take over Canada:

Because Canada and the United States, that would really be something. […] We’re spending hundreds of billions a year to take care of Canada. We lose — in trade deficits we’re losing massive […] you know, they make 20 percent of our cars. We don’t need that. […] [So] they should be a state. That’s what I told Trudeau when he came down. I said what would happen if we didn’t do it. He said Canada would dissolve. Canada wouldn’t be able to function.

I’m inclined to say that Trump isn’t really going to attempt to annex Canada, and it’s probably just an Overton-window-shifting, door-in-the-face tactic that he’s using to try to make his trade war more palatable. But then again, Justin Trudeau seems to think Trump is serious, and it’s not totally outside the realm of possibility that he’d try to secure his legacy through territorial expansion. Attempts to annex Canada have actually been so common throughout American history that there’s an entire Wikipedia page about it. And Manifold gives it a 6% chance of happening by January 2029, so I figure it’s at least realistic enough to write a blog post about it.

So, what does the international relations literature have to tell us about Trump annexing Canada?

The short answer is not much. You might be surprised given how much conventional IR theory is supposed to be about states’ struggle for survival in the international system, but scholars have barely grappled with how and why some states cease to survive. Almost 20 years after publication, the seminal works on the topic — Tanisha Fazal’s 2004 paper “State Death in the International System,” and her 2007 monograph State Death: The Politics and Geography of Conquest, Occupation, and Annexation — are, to my knowledge, still the definitive treatment in the scholarly literature. (Much like the topics of fertility and stereotyping, it’s up to us lowly bloggers to push the field forward…)

Fazal’s primary finding is that the most common victims of state death in the international system are so-called “buffer states” located between two powerful and enduring rivals: for example, Poland between Germany and Russia, or Mongolia between China and the Soviet Union. Since a rival can never know with certainty what the other rival wants or believes, neither of them can be assured that the other isn’t going to attempt to dominate the buffer and gain the upper hand in a potential conflict. Therefore, even if the rivals would mutually prefer having a buffer between them to cool tensions, each rival has an incentive to preempt the other and occupy or annex the buffer state to prevent its adversary from gaining a first-mover advantage.

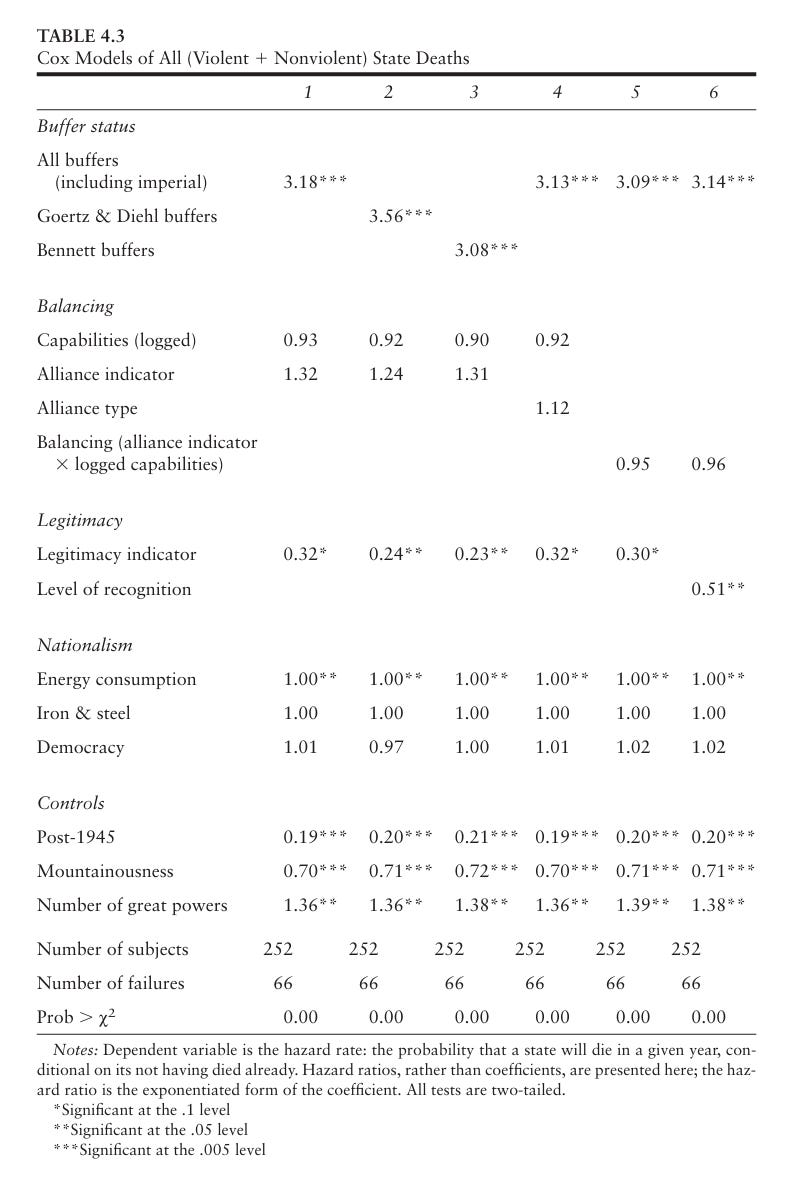

Since 1816 (the beginning of Fazal’s data set), about 40% of violent state deaths have been buffer states, and about 40% of buffer states have died. In any given year, a buffer has been about 3.18 times as likely to die, and 2.34 times as likely to die violently, as a non-buffer, regardless of what capabilities or allies it has, or how nationalistic its population is.

The buffer state theory of state death supports the explanation for the war in Ukraine offered by some heterodox analysts and commentators like political scientist John Mearsheimer. Ukraine is a buffer between Russia and NATO, and Vladimir Putin feared that if he didn’t attempt to annex Ukraine, it would be dominated by NATO and used as a springboard to threaten Russia. Since Putin couldn’t know with certainty that NATO’s intentions were benign, he felt that he had to invade Ukraine to ensure Russia’s security.

This explanation doesn’t work for Canada, however. Unless Trump knows something we don’t, and Santa Claus actually does live at the North Pole, and his toy factories are quietly being repurposed for arms manufacturing and aimed against the United States, then Canada isn’t a buffer state. And Fazal’s theory predicts it shouldn’t end up on the receiving end of threats to its survival.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to United States of Exception to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.