Influence Is Mostly Signaling

Yes, you should get a PhD.

Let’s say you have an above average verbal intelligence and you’re willing to accept low pay in exchange for social impact and intellectual freedom. If you’re a Substack blogger and you talk about philosophy, social science, or politics (in that order), this probably describes you. What sort of educational path is best?

If you ask people who have accomplished the very thing you want to do, they’ll tell you that you shouldn’t get a doctorate. You should just start writing for educated laypeople.

Bryan Caplan — who has a PhD in economics from Princeton — asks the following of any prospective grad student who comes to him for advice:

Question #1: “What is your career goal?” […] If they say they want to work in a think tank, I respond, “This might be a good idea, but you could plausibly skip the whole program by launching a successful Substack. Why not try that instead?”

Richard Hanania — who has a JD from UChicago and a PhD in political science from UCLA — says something similar. If you want to have an impact on government or society, don’t go into academia. And don’t spend five or six years of your early career training to become an academic. Just start writing.

You can understand why somebody with a PhD would say this. Doctoral programs are designed to train new academics to produce knowledge — not to become, as F. A. Hayek put it, “professional second-hand dealers in ideas.” Grad students in Caplan and Hanania’s fields get a lot of training in statistical modeling and almost none in popular communication.

You might think Caplan and Hanania probably know what they’re talking about because they’ve experienced firsthand how irrelevant a doctoral education is for a career as a public intellectual.

But if you’re the type of person who thinks like a researcher, you might also suspect that they don’t know what they’re talking about because they’ve never tried succeeding as an intellectual without a PhD.

In an ideal world, you’d be able to suss out which of these inklings is right by recruiting some precocious young lads and lasses (and l’nonbinaries?) to participate in a randomized controlled experiment where you see how pursuing a PhD affects one’s success at building a high-impact, high-autonomy career, with rigorous operational definitions for “impact” and “autonomy.” Or you’d find some way to observe how many people there are who want to become a public intellectual, how many of them get a PhD and don’t, how many of each group succeeds and to what extent, and a lot of other figures that are really hard to know that you’d have to fit into a multivariable regression.

In a truly ideal world — a deep utopia, if you will — every aspiring intellectual would be able to run Bostrom-like simulations that would tell them if getting a PhD would be net good or bad, how much impact and autonomy they would have, and whether it would help them make friends.

Tragically, we don’t live in an ideal world. The only question above where we have a definitive answer is whether a PhD helps you make friends. (It does, but only if you want to be friends with nerds like yourself.) If you want to know whether getting a PhD is worth it, you have to rely on some bad old-fashioned hypothesis testing.

First, estimate the proportion of people in the population “potential public intellectuals” who have a doctorate. Then find a representative sample of successful public intellectuals and look into their credentials. And finally, do whatever statistical voodoo you need to figure out whether to reject the null hypothesis. If your result is statistically significant and more people have a doctorate than you would expect, that’s a good sign that something about a doctoral credential helps you succeed in the marketplace of ideas.

The Baseline

What percentage of people in the category “potential public intellectuals” has a doctorate? (Here, a “potential public intellectual” is anyone with the requisite intelligence for a high-impact, high-autonomy job.)

Considering that this population includes people like Thomas Friedman, the IQ threshold might not be too high. Let’s assume that a potential public intellectual is anyone with an IQ above 130. (If that seems too low, consider that an unscientific poll of right-wing weirdos estimates Hanania’s IQ at only 130. This is very poor evidence, but we don’t exactly demand accuracy or precision here.) This is just under 2.3% of the population.

About 2.1% of Americans aged 25 or older have a doctorate, according to the Census Bureau. Just over half of these people have a PhD and the remainder have either a JD or an MD or a fake degree like an EdD. Wikipedia says Alan Kaufman found that the average IQ of doctorates is 125. (I can’t track down the original source, but again, we’re not looking for precision.) If the intelligence of doctorates is normally distributed with a standard deviation of 15, just over a third of doctorates have an IQ of at least 130. Let’s round this up to half to be conservative. This is about 1.1% of the population, or just under half (47%) of all potential public intellectuals.

These are very uncertain figures, so we’ll use a very stringent significance level (α = 0.01). We can reject the null hypothesis if there’s no more than a 1% chance that we would get results as extreme as the results we observe, assuming 47% of actual public intellectuals have a doctorate.

The Population

How do you identify who’s a public intellectual? (Remember, our criteria here are people with highly impactful and highly autonomous careers.) Caplan might suggest that you look at the most popular Substacks. But anyone can make a blog and get popular. He who must not be named has nearly as many subscribers as Matt Yglesias. The top five “Health Politics” Substacks are all written by anti-vaxxers. Simply having a readership and generating revenue doesn’t mean you’re reaching the movers and shakers of the world who influence consequential decisions.

Maybe you think we can find people who fit our criteria if we look at the institutions traditionally associated with high verbal intelligence: academia, think tanks, and the media. When I asked ChatGPT and Claude where I could find members of the intelligentsia, these are the first three institutions they listed. And it makes sense that this is where most intellectuals would be found.

But we aren’t interested in just anyone in these professions. Plenty of academics never deign to leave the ivory tower, and even if they did, there wouldn’t be much purchase for their ideas in government and society. If you work at a think tank, you hardly have intellectual freedom; if you stray too far from a donor’s interests or your employer’s ideological bent, you’ll soon find yourself out of a job. Journalists who wish to maintain a good reputation have to avoid running afoul of media owners, advertisers, sources, and their colleagues. And only a small number of think tankers and journalists’ work ever makes an original or interesting contribution to the discourse.

What we’re really interested in are the members of the intelligentsia whose ideas are taken seriously by the smart, high-society laypeople who disproportionately hold the country’s college degrees and professional-managerial class jobs, who enjoy high culture, set and enforce the tone of political discourse, and occasionally trouble to read high-brow general interest magazines and newspapers of record. What we’re looking for are the thought leaders and cultural arbiters of the upper middle class.

Since 2005, the quintessentially upper-middle-class Foreign Policy and Prospect magazines have run a quasi-annual poll of their readership to determine who are the world’s most influential living public intellectuals. In recent years, Prospect has run a poll to name “The World’s Top Thinkers,” which includes people who made significant public-facing intellectual contributions specifically in the past year.

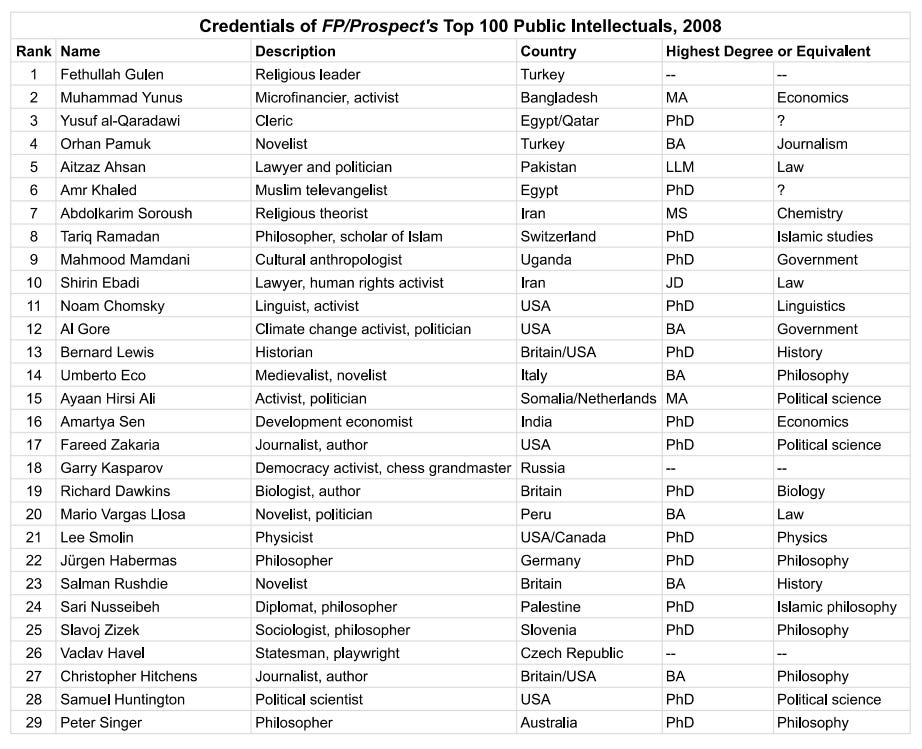

These polls allow us to test whether having a doctorate helps someone become a successful public intellectual both before and after the democratization of communications technology that occurred in the late 2000s and 2010s. Below, I analyze the educational credentials of people named in the 2008 FP/Prospect poll of the world’s top 100 public intellectuals, as well as Prospect’s polls of the top 25 thinkers of 2022 and top 50 thinkers of 2024.

The Credentials

I reviewed the credentials of each public intellectual by searching on their Wikipedia page and Google to determine the highest degree they had achieved. Where I could also find the field in which they earned their degree, I recorded both the degree achieved and the relevant field of study. The results are shown in the tables below:

In the 2008 FP/Prospect poll of the top 100 public intellectuals, 65 have a PhD or a DPhil. Another four have an MD or a JD. The most commonly represented fields among doctorates are economics (13), political science and government (13), philosophy (9), and history (7). In the 2022 and 2024 Prospect polls of 74 total top thinkers, 42 have a PhD or a DPhil. Another four have an MD or a JD. The most commonly represented fields among doctorates are philosophy (7), economics (6), history (6), and political science and government (4).

This means that 69% of top public intellectuals in 2008 and 62% of top thinkers in 2022 and 2024 had a doctoral degree.

The Statistical Test

According to ChatGPT, the right statistical test to use here is a one-proportion z-test. This is used to compare an observed proportion of a sample (successful public intellectuals) to a hypothesized proportion of a population (potential intellectuals).

For the 2008 sample, the p-value is extremely small and the result is statistically significant. The same is true of the 2022 and 2024 sample. It is highly unlikely that the observed result occurred due to chance alone or that there isn’t a genuine correlation between having a doctorate and becoming a successful public intellectual.

Conclusion

If you have a high verbal intelligence and you value social impact and intellectual freedom, earning a doctorate may help you fulfill your career goals. Significantly more public intellectuals have doctorates than one might expect based on IQ alone.

This may sound obvious, but it’s actually deeply puzzling. A doctoral education involves little training in popular communication. Arguably, earning a doctorate poses a significant opportunity cost to aspiring intellectuals who have to spend a great deal of time in graduate school when they could be honing their brand and building an audience among educated laypeople instead.

Two possible explanations come to mind. First, being involved in academia may provide an aspiring intellectual with invaluable access to the media and government through their academic network. If you earn a PhD, you know other people who also have a PhD who can connect you with people you need to know to get on cable news, publish your op-eds, and set up meetings with influential politicians and their staffers.

Second, influence may actually be all about signaling. Government officials and the public want to follow the advice of smart people, and one of the best ways to know if someone is smart is to check if they have a fancy degree from a world-class university. Caplan famously suggests that about 80% of the value of education is to show employers you’re the type of person who can earn a degree. Why should it be any different with the public at large? Dr. Degree Haver, PhD, sounds a lot more credible than a simpleton like Mr. Good Ideas.

Interesting. The signaling may be a lot more important than I thought! It could also be a bit of the fact that the types of people who pursue PhD ("hard workers") are the same type of people who pursue being a public figure through writing.

The was really fascinating, thank you! My own explanation for this phenomenon…there just aren’t that many environments in the private sector that really sharpen someone’s intellectual position and viewpoints as deliberately as the PhD model.

The signaling must help—and the connections and network from a PhD—but it’s also the 3–7 years (depending on what country/discipline someone got their doctorate in) that helps someone do original research and generate novel points of view.