At this point, everyone knows the unipolar moment is over. Even Marco Rubio, the nominatively determined manager of the Rules-Based International Order (RuBIO) and heir to the Project for the New American Century, admits that the post-1989 world order was a historical anomaly. Yours truly — notable as much for my insouciance toward the erosion of American hegemony as for my “ha[ving] really great insights into Jeff Tiedrich and the history of libertarianism” — was recently converted to a mild skeptic of unipolarity by Jennifer Lind’s article in International Security, “Back to Bipolarity: How China’s Rise Transformed the Balance of Power.”

Lind, like any good scientist, makes the unintuitive seem obvious. She deserves credit foremostly for not continuing to litigate the best way to deductively measure national power and then, based on that, trying to categorize great powers, superpowers, potential superpowers, and “emerging potential superpowers” as her colleagues have done for the past 35 years. Rather, Lind starts from the premise that we can know who the great powers have been throughout history and then works her way backward to determine which measures correctly identify great powers and what the thresholds of greatness are.

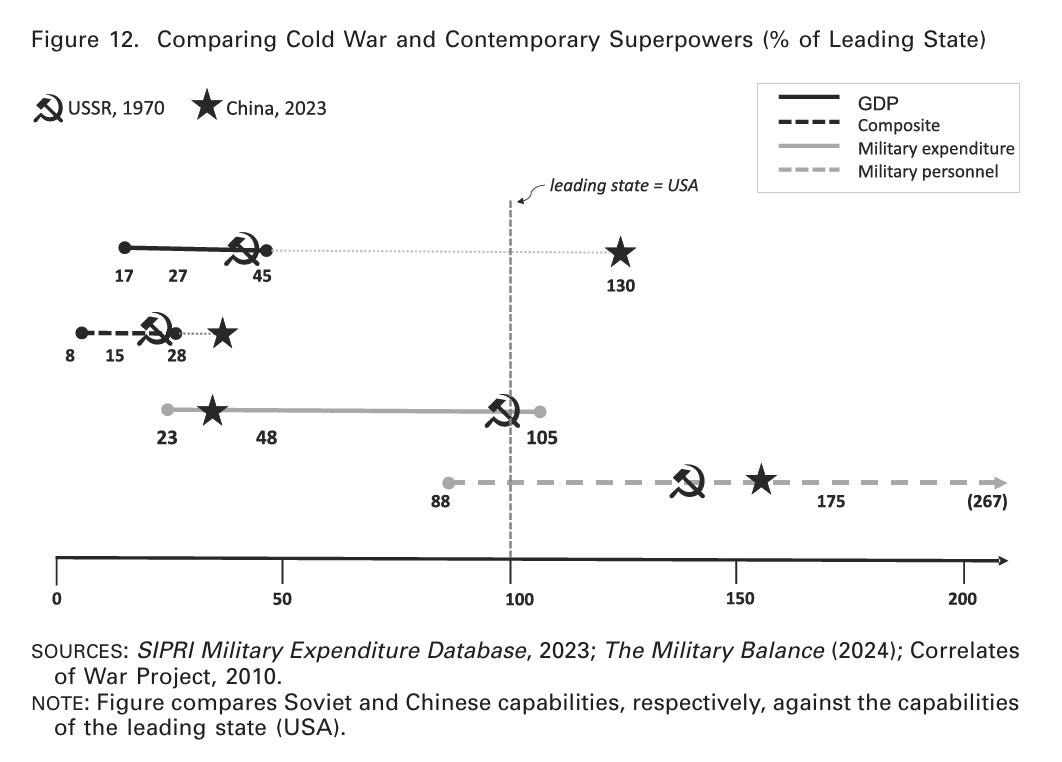

The political science discipline already has a robust data set of “major powers” that it uses to code international conflicts that more or less reflects the consensus among political scientists and historians. The basic criterion for great powerhood in the data set is a lot like the standard for pornography — you know it when you see it — but unlike pornography, there’s actually a great deal of agreement as to who the great powers have been. According to the data set authors Melvin Small and J. David Singer:

[A]ll students of world politics use, or appreciate the relevance of, the concept of “major power.” […] Although the criteria for differentiation between major powers and others are not as operational as we might wish, we do achieve a fair degree of reliability on the basis of intercoder agreement. That is, for the period up to World War II, there is high scholarly consensus on the composition of this oligarchy.1

Thus, the intuitive definition of “great power” ought to be a state that exceeds some minimum threshold along a non-arbitrary metric or metrics for great powerhood that includes the great powers in the data set but doesn’t include states not in the data set, save for a few inevitable false positives and negatives.

With regard to “non-arbitrary metrics,” there’s no shortage of options. Political scientists have long relied on GDP to measure a state’s economic and latent military power, but some scholars have recently proposed measuring power according to net rather than gross resources by using GDP times GDP per capita, or stocks of resources rather than flows by using the World Bank’s Changing Wealth of Nations statistic. On the military side, some use the Composite Index of National Capability, or CINC, which measures a state’s ability to wage war — but this measure has increasingly fallen out of favor because it privileges industrial capacity and results in some dubious codings like China being more powerful than the United States since 1996. There’s also the amount of money a state spends on its military and the number of military personnel it has under arms.

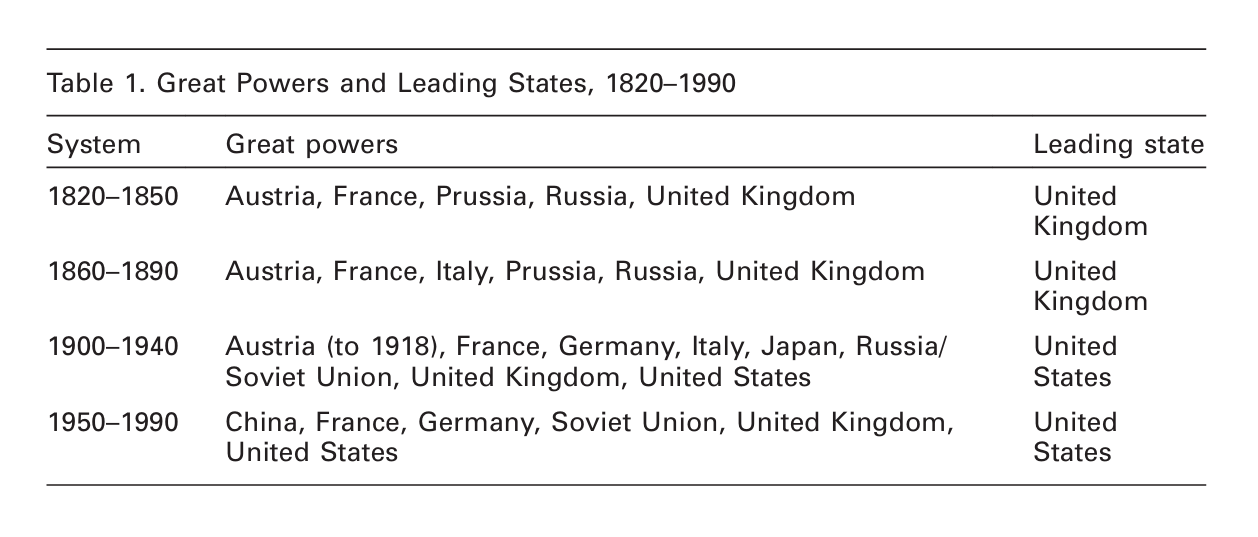

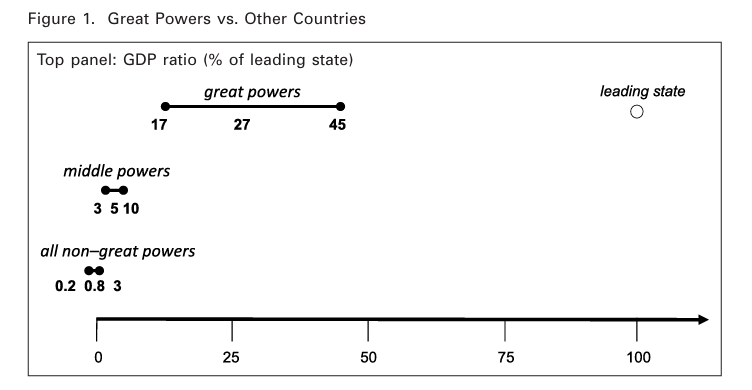

Lind compares each great power’s economic and military capabilities along multiple dimensions to the capabilities of the leading state during each decade from 1820 to 1990. To make sure a statistic doesn’t count too many great powers as non-great powers or vice versa, she compares where the “normal range” of a statistic (between the 25th and 75th percentile) lies for historical great powers versus where it lies for middle powers and non-great powers. If the ranges overlap, the statistic doesn’t have good predictive value. If they don’t overlap, we consider it valid. Two economic and two military statistics end up predicting most great powers without turning up too many false positives or negatives.

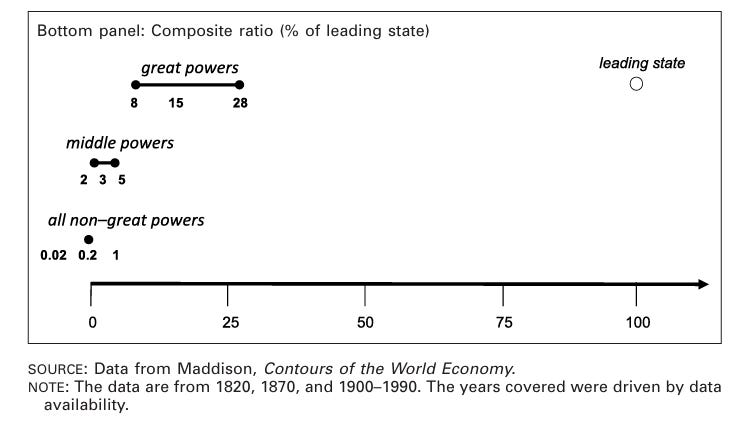

Along the relevant economic dimensions, states don’t actually have to be close to the leader to satisfy the intuitive requirements of great powerhood. Since 1820, half of all great powers have had a GDP within a range of 17% to 45% of the leading state, with a median of 27%. If you also consider economic sophistication and measure a state’s capabilities according to its GDP times GDP per capita, most great powers have only needed capabilities between 8% and 28% as high as the leading state to qualify as a great power, with a median of 15%.

Along the military dimensions, great powers have had to marshal a much greater level of force compared to the leading state to exceed the threshold for great powerhood, with half of all great powers spending between 23% and 105% as much as the leading state on their militaries and fielding between 88% and 267% as many military personnel, with a median military expenditure ratio of 48% and a median personnel ratio of 175%. (In other words, great powers have often outspent and typically outrecruited the leading state but still not exceeded the leader’s international influence.)

Lind finds that China — and no other state — currently far exceeds the economic threshold for great power status and sits within the normal range for military capabilities. She says this shows that China is a revisionist actor in terms of the military balance of power, as China’s post-1996 military buildup contrasts to the constitutional pacifism and restraint of Japan and Germany after World War II, despite their disproportionate economic might. In fact, Lind says China is not merely a great power but a superpower on par with the Soviet Union, and the competition between the United States and China is likely to be even more intense than the Cold War:

Today, China exceeds the Soviet Union on almost every dimension of national power. China has vastly stronger economic capabilities than the Soviet Union ever did. China lags the Soviets only for military expenditure, but, importantly, China spends an estimated 1.7–2 percent of its GDP on defense (relative to the Soviet Union, which spent a punishing 12–14 percent). If competition with the United States grows, China has tremendous resources on which to draw to create more military power.

In total, China has a GDP adjusted for purchasing power parity 130% as large as the United States, compared to just 37% for the Soviet Union at its peak. China also has a GDP times GDP per capita 36% as large as the United States, which exceeds the 75th percentile for historical great powers. Its military expenditure is 32% as high as the United States and it has 153% as many military personnel, both below the median but higher than the 25th percentile for historical great powers. The closest state after China — either India, Germany, or Russia, depending on your metric — fails to match at least the 25th percentile on either the economic or military dimension.2 If this is all the data you have to go on, Lind says you ought to presume the world is bipolar and China will behave like the Soviet Union, attempting to upend the international order, project power within its region, and promote its ideology around the world, unless you have good reasons to think otherwise.

On the first point — that the world is “bipolar” (setting aside what that’s supposed to mean, since it’s operationalized as being analogous to what we think it means) — I suppose Lind is correct by definition. But that only reveals how meaningless the question of bipolarity is as Lind poses it. What’s more important is what we think Sino-American bipolarity is going to look like. And on that point, Lind is totally off the mark: The U.S. relationship with China is not like the Cold War — at least, it doesn’t have to be like the Cold War as long as the United States doesn’t decide to make it that way. The problem with comparing China to the Soviet Union is that China occupies a completely different security environment than the Soviets did, apparently has very different interests, and behaves a lot differently. You can see this for five reasons.

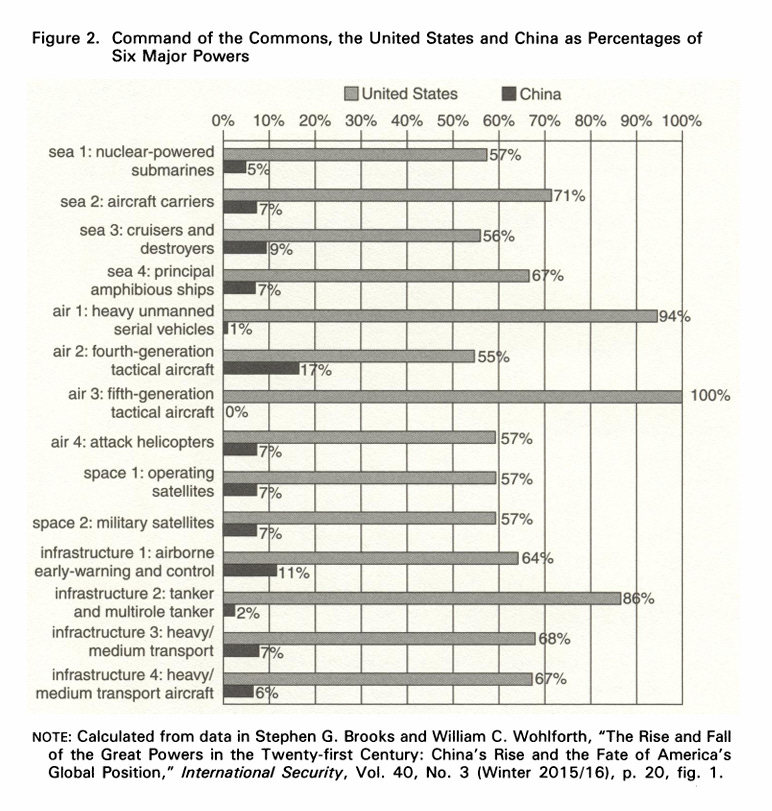

First, if China is going to project power in its region, then unlike the Soviet Union, it’s going to have to project power across water. This is significantly more difficult than projecting power over land, and it ought to raise the threshold for China to be considered a military great power or superpower. China passed the historical 25th percentile military spending threshold in 2014, but at that point it barely had any of the sophisticated platforms it would have needed to conquer territory in its region or seriously contest American command of the global commons. Even today, China’s most important capability is merely that it could prevent the United States from operating in East Asia, not that it could dominate neighboring countries like Taiwan.

In fact, the very same technologies available to China to deny U.S. access to East Asia are also available to China’s adversaries to deny China access to its periphery. According to the RAND Corporation, anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems like surface-to-air missiles, anti-ship missiles, and drones can destroy about 50 times their value on average in power projection platforms. Unless you expect China’s long-run GDP to be 50 times greater than the other states in the region, you shouldn’t think it’s likely that China is going to try to seize maritime territory in East Asia as the Soviets did in Eastern Europe.

Second, although Lind claims to show China harbors revisionist interests toward the global military balance of power, according to Lind’s figures, China is massively underinvesting in its military compared to the historical great powers and especially compared to the Soviet Union. The median great power has had a GDP 27% as large as the leading state but spent 48% as much on its military, or 1.78 times as much as a share of GDP. The Soviet economy at its peak was 37% as large as the United States, but the Soviets spent 100% as much as the United States on their military, or 2.70 times as much as a share of GDP. China has a GDP 130% as large as the United States, but it spends only 32% as much on its military, or 0.25 times as much as a share of GDP. To put it another way, if China was a NATO ally of the United States, it would never hear the end of its failure to spend at least 2% of GDP on defense.

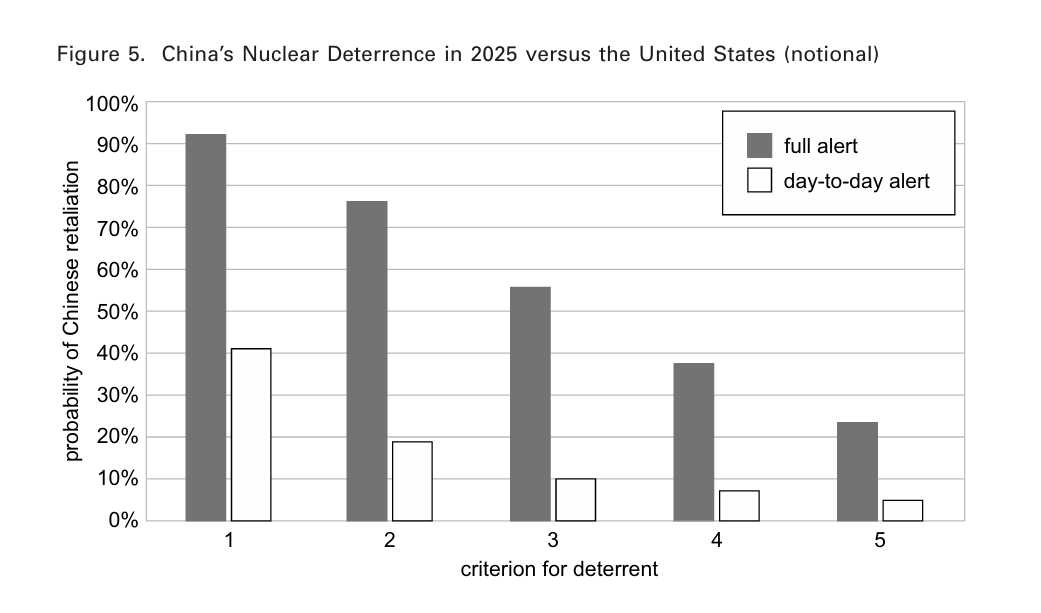

Third, in stark contrast to the nuclear politics of the Cold War, China is especially conservative in its approach to nuclear weapons. In addition to maintaining an unconditional no-first-use policy — the only such policy in the world — China has long accepted that even its retaliatory capability may not be assured. As of 2020, it was estimated that if China continued to develop its nuclear arsenal, then by 2025 there would only be a 40% chance that it could absorb a nuclear strike while on day-to-day alert and have enough surviving infrastructure to launch a single warhead at the United States in retaliation.

China has modernized and expanded its arsenal since 2020, but this does not reflect a fundamental revision of Chinese nuclear posture. Rather, according to an analysis of Chinese-language nuclear strategy documents by Western security experts, “China’s assessment of the force levels required for deterrence appears to have changed.” This is because the United States under the Trump and Biden administrations abandoned longstanding nuclear arms control agreements, sought to develop low-yield nuclear weapons to lower the threshold for nuclear use, and invested in missile defenses and conventional precision-strike capabilities to undermine the usefulness of China’s deterrent. China, unlike the United States and the Soviet Union, does not see nuclear weapons as a core instrument of national power and does not seek nuclear superiority.

Fourth, contra Lind, China is not interested in exporting its ideology like the Soviet Union was, nor does China have a “toolkit for influencing operations and exporting authoritarianism [that] far exceeds that of the Soviet Union.” The Chinese state’s primary source of legitimacy is nationalism, not universalist ideology like Marxism-Leninism. Unlike Soviet communism (and American liberalism, for that matter), Chinese nationalism does not have a crusader impulse and does not impel its adherents to spread ideology around the globe. China has mainly sought to promote its image abroad through peaceful diplomatic exchanges and economic inducements, while doing business with states that exhibit a wide range of governance strategies. To the extent that it’s used coercive means and transnational repression to attempt to promote its image and silence dissent in democratic countries, it’s only polarized international publics against it and its international conduct.

Thus, while it may be accurate to say China seeks to make the world safe for authoritarianism and make it easier for authoritarian regimes to survive, it is not accurate to say China seeks to make the world authoritarian in the same way the Soviet Union promoted communism or the United States has sought to transform other countries in its own image. Helping authoritarian regimes engage in repression is a bad thing, to be sure, but it’s not seriously threatening to the longstanding pillars of international peace.

Finally, unlike the Soviet Union, China is largely satisfied with the international order and supports most of the post-1945 norms and institutions, often with more consistency than the United States. Lind warns that China has countered the United States in part by “doubl[ing] its memberships in international institutions from 1990 to 2010,” “becom[ing] a leader in the United Nations,” and “promoting ideas about state capitalism, respect for sovereignty, and ‘anti hegemonism,’” and highlights the following quote by a Chinese government official as evidence that China seeks to overturn the rules-based international order:

In the words of China’s Foreign Ministry, “The United States has developed a hegemonic playbook to stage ‘color revolutions,’ instigate regional disputes, and even directly launch wars under the guise of promoting democracy, freedom and human rights. […] It has taken a selective approach to international law and rules, utilizing or discarding them as it sees fit, and has sought to impose rules that serve its own interests in the name of upholding a ‘rules-based international order.’”

But this shows precisely the opposite of what Lind says it does! Are we seriously supposed to believe China seeks to undermine international norms and institutions because it… supports international norms and institutions? Or because it criticizes the United States for failing to respect the basic principles of the international order? Or are we supposed to believe that “respect for sovereignty” is a bad thing and not the central organizing principle and most important noble lie of the international system over the past 400 years? It takes an unreasonably uncharitable and stereotypical view of Chinese foreign policy to make the argument make sense.

In a very narrow respect, Lind is correct. The world may be “bipolar” — whatever that means — but bipolarity between the United States and China need not be a repeat of the Cold War. This is why I only consider myself a mild skeptic of unipolarity. It is not a foregone conclusion that the Pax Americana has to end. Rather, if the United States turns around its foreign policy and plays its cards right — continues to prioritize economic growth and promotes commercial globalization, engages in strategic restraint and supports multilateral institutions, avoids unnecessarily antagonizing its adversaries or precipitously withdrawing from alliances, and refrains from running roughshod over sovereignty norms or seriously upsetting the nuclear balance of power — then everything is going to be fine. To the extent that the international order is falling apart, the blame primarily lies with one actor. The most powerful enemy of the United States and the Pax Americana is not China, but the United States itself.

Melvin Small and J. David Singer, Resort to Arms: International and Civil Wars, 1816–1980 (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage, 1982), 45.

In fact, no state other than China even approaches 23% of the U.S. military budget, the 25th percentile for historical great powers.

China has done some really terrible things like sell me cheap products and buy my countries debt at subsidized rates. The horror!

If we don’t watch out they might start selling me cheap electric vehicles!

Look, if we didn’t have nukes then maybe I would be all worried about them taking over the world. But we do have nukes. An invasion of Taiwan would end 5 minutes after it started. And they don’t even have a good reason to try.

There are some issues with the Soviet military spending numbers here

- They're cited as coming from Holzman (https://doi.org/10.2307/2538679), but they're actually CIA estimates he's quoting. Holzman explicitly states that he thinks they're 1-2% too high

- They are contemporary estimates of spending in the 1982 budget - deep into the cold war, and well past its hottest point. CIA estimates from 1973 are 6-8% of GNP.

- CIA estimates at the time were based on direct costing - which is extremely sensitive to how you do dollar-ruble comparisons, when you get your index prices from, etc. And is questionably meaningful, in a Soviet-style planned economy. Realistically, we don't actually know what the Soviet military cost them, and neither did the Soviet government.