America’s new secretary of state, Marco Rubio, says that if he was in charge in 2003, knowing what we know now, he wouldn’t have invaded Iraq. Seems sensible, right? But he doesn’t think invading Iraq was a mistake. That’s because you have to judge people for their past decisions based on the information they had access to at the time. And the information at the Bush administration’s disposal suggested that invading Iraq was a slam dunk. Rubio said:

I doubt very seriously that the president would have gotten, for example, congressional approval to move forward with an invasion had they known there were no weapons of mass destruction. That doesn’t mean he made the wrong decision, because at the time he was presented with intelligence that said there are weapons of mass destruction.

Rubio’s specific explanation fails: The Bush administration should have known there weren’t weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. The evidence was so flimsy that even if they didn’t manufacture it themselves — a probable explanation — the only reason they would have had to believe it is that they wanted to invade Iraq whether Saddam had WMDs or not and they simply needed a pretext for it. This would explain why, for example, Colin Powell claimed in his decisive speech to the United Nations that Saddam had a fleet of mobile bio-weapons-producing labs on the backs of truck trailers even though international inspectors said that wasn’t true and the primary source for the claim was an Iraqi exile known as “Curveball” whose German debriefers judged him to be unreliable.

Rubio nevertheless has a point. It is not inconceivable that ex ante, the Iraq War was a good idea. I don’t think that’s true, and if you keep reading, you’ll learn why. But in the spirit of cognitive empathy, and following very failed Substacker

’s recent ideological Turing Test for socialism, I want to make the strongest possible case that the Iraq invasion was a good idea. This means I’ll be taking the perspective of someone in the year 2003, but I won’t be relying on the then-already-discredited notion that Saddam had WMDs or that Iraq was connected to al-Qaeda and 9/11. Nor will I be making the argument Bryan Caplan made in his steelman case for the Iraq War — that it would be good for the United States to bring Enlightenment to the Muslim world — which I find utterly unconvincing because it makes no attempt to weigh costs against benefits.The steelman case for the Iraq War is as follows:

Every ten years or so, the United States needs to pick up some small crappy little country and throw it against the wall, just to show the world we mean business.

So goes the Ledeen Doctrine, the tongue-in-cheek “doctrine” named after the neocon godfather and “Freedom Scholar” at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, Michael Ledeen, as it was attributed to him by National Review columnist Jonah Goldberg in 2002.

The logic of the Ledeen Doctrine is that, for the United States to remain the world’s sole superpower and deter challenges to its hegemony, it must continuously demonstrate its strong capabilities and willpower to a global audience lest its authority be brought into question. Should it fail to demonstrate its power, rogue states and competitors may begin to assume the United States isn’t up to the job of world policeman and start running roughshod over the rules of international order. This would result in some extremely negative consequences, including harder-to-solve collective action problems, less provision of global public goods, less globalization and slower economic growth, more arms races and regional conflicts, increased risk of great power war, and a long-term diminished ability of the United States to shape international norms and institutions according to its values.

Goldberg recalls that Ledeen first articulated the doctrine in a speech at the American Enterprise Institute in the early 1990s. But it had been percolating in Washington ever since some two decades prior when Uncle Sam was dealt an embarrassing blow by a motley band of jungle-dwelling rice farmers in the lower Mekong River basin. Throughout the 1980s, U.S. leaders had picked up a few crappy little countries to throw against the wall. But the lesson never stuck until 1991, when the decisive allied military intervention against Iraq informally set off Charles Krauthammer’s “Unipolar Moment.” After U.S. bombers laid waste to the country, systematically destroying civilian infrastructure paid for in part by American farm subsidies, Poppy Bush declared that the United States had established a new world order in which “the specter of Vietnam [had] been buried forever in the desert sands of the Arabian Peninsula.”

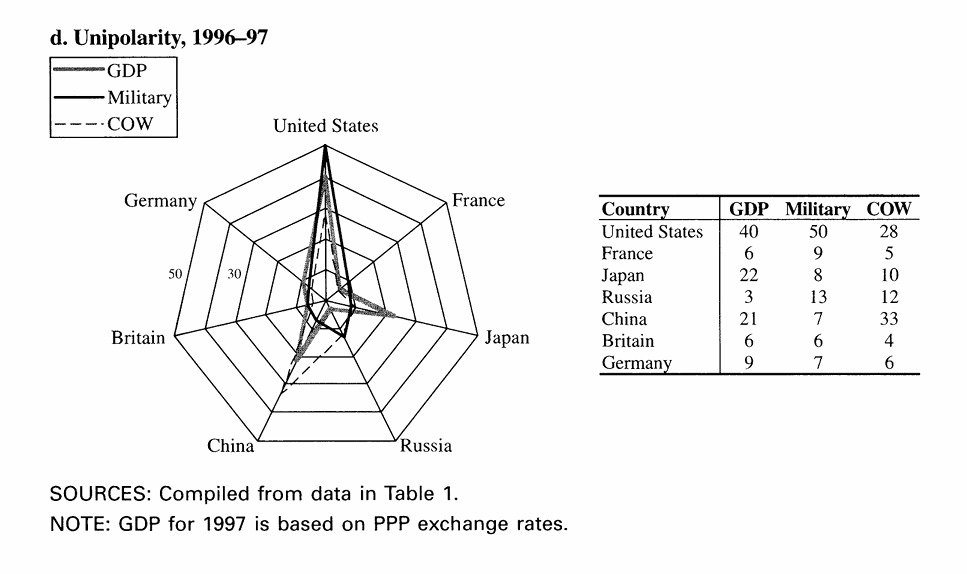

The sheer concentration of economic and military power in the United States after the Gulf War was positively intoxicating to American policymakers. Paul Kennedy, the legendary British historian of international relations, determined that: “Nothing has ever existed like this disparity of power; nothing […] I have returned to all of the comparative defense spending and military personnel statistics over the past 500 years that I compiled in The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, and no other nation comes close.”1 Political scientist Bill Wohlforth, then a strapping young assistant professor at Georgetown, calculated in 1999 that the United States had a greater military budget and far greater investment in defense R&D and power projection capabilities than every other potential great power combined. Even the academy’s most outspoken skeptic of unipolarity, Christopher Layne, admitted that the United States might remain the world’s sole superpower for as long as 50 years — although he described this as “a reasonably short time.”2

The United States quickly seized on its unprecedented international position to attempt to refashion the world order closer to its own liking. It created and expanded liberal institutions like NAFTA, APEC, NATO, and the WTO in order to integrate secondary states into its orbit and reassure them of its benign intentions. At the same time, it sought to maintain military preponderance to deter any other states from attempting to challenge its role as the global hegemon. The elder Bush administration’s draft Defense Planning Guidance FY 1994–99, leaked to the New York Times in 1992, advised that the United States “must maintain the mechanisms for deterring potential competitors from even aspiring to a larger regional or global role.” The United States had surpassed — as Wohlforth put it — a “threshold concentration of power” beyond which it was hopeless for other states to attempt to balance. Even China sought to be accommodated and integrated into the so-called “liberal international order.”

The American self-narrative of perpetual global leadership, and the generalized sense of deterrence that U.S. leaders believed it produced among potential counterhegemonic challengers, made the 9/11 attacks particularly jarring. Political scientist Ahsan Butt writes that:

A sense of impregnability was necessary to sustain the idea that the United States was the region’s, and arguably the world’s, unipolar power. The terrorist attacks of 9/11 punctured this sense of American invulnerability and dominance in the collective thinking of the US body politic if not other observers. As [political scientist Ron] Krebs asks rhetorically, “How much of a superpower could America be if 3,000 of its citizens, residents, and visitors had died in a single day?”3 On September 11, 2001, the United States was still materially hegemonic, but its status and prestige were considerably damaged by the fact that fewer than two dozen men, a “rag-tag cabal of Middle Eastern terrorists”4 armed with box cutters, destroyed the symbols of American capitalism and military power.

American officials and foreign policy experts immediately recognized that, in order to maintain their credibility and deter further challenges to the hegemonic order, they needed to make an example out of somebody. Afghanistan alone wouldn’t cut it, since it was a bit too crappy and the invasion was a proportional response to 9/11 that didn’t quite promote the image of a madman theory hegemon that nobody wants to mess around with. As Butt recounts, Pentagon officials were already talking about going beyond Afghanistan mere hours after the first plane hit the North Tower:

As [secretary of defense Donald] Rumsfeld privately said on the evening of 9/11, “We need to bomb something else [other than Afghanistan] to prove that we’re, you know, big and strong and not going to be pushed around by these kinds of attacks.”5 […] On September 12, Rumsfeld’s thinking was that “the Bush administration needed to demonstrate that the United States had the will to fight beyond Afghanistan.”6 According to [under secretary of defense for policy Doug] Feith, “Rumsfeld wanted some way to organize the military action so that it signaled that the global conflict would not be over if we struck one good blow in Afghanistan.”7 Similarly, Feith wrote a memo to Rumsfeld in which he “expressed disappointment at the limited options immediately available in Afghanistan” and “suggested instead hitting terrorists outside the Middle East in the initial offensive, perhaps deliberately selecting a non-al Qaeda target like Iraq.”8

Over three dozen top neoconservative intellectuals, including Bill Kristol, Francis Fukuyama, Donald and Robert Kagan, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Charles Krauthammer, Norman Podhoretz, and Midge Decter, also instructed the administration in a September 20, 2001, open letter that “even if evidence [did] not link Iraq directly to the attack,” failure to make “a determined effort to remove Saddam Hussein from power [would] constitute an early and perhaps decisive surrender in the war on international terrorism.” Jonah Goldberg, in his “Ledeen Doctrine” column, likened international politics to a prison yard in which security is gained through demonstrations of force. Thus: “The United States needs to go to war with Iraq because it needs to go to war with someone in the region and Iraq makes the most sense.”

The steelman case for invading Iraq goes that, according to the information we had at the time, it was reasonable to believe that if the United States had not invaded Iraq, it would have invited costly challenges to the international order by rogue states and potential great power competitors unpersuaded of its resolve and capabilities after 9/11. Iran, Libya, North Korea, and Syria would have intensified their pursuit of nuclear weapons, heightening the threat of WMD proliferation that Krauthammer declared was even more concerning than the threat previously posed by the Soviet Union. Some rogue states might have transferred nuclear weapons to terrorists; in 2004, political scientist and former Pentagon official Graham Allison estimated that the probability of a successful nuclear terrorist attack against the United States over the next decade, if the United States failed to take action to prevent one, was at least 51%.9 If the United States did not demonstrate that it remained above Wohlforth’s “threshold concentration of power,” China’s peaceful rise may have stopped being so peaceful. Japan, South Korea, and European NATO allies may have come to believe the United States was no longer willing or able to uphold its security guarantees and begun to re-militarize or seek nuclear weapons to defend themselves.

This all would have had disastrous effects for international peace and security. Probably the most concerning is that the abdication of international leadership by the United States would have hastened the end of the post-1989 or even post-1945 international order and risked China contesting the mantle of global leadership. Allison finds that over the past 500 years, great power transitions have resulted in war 12 out of 16 times. Moreover, “[w]hen the parties avoided war, it required huge, painful adjustments in attitudes and actions on the part not just of the challenger but also the challenged.” Had the United States lost hegemony, it would also have lost its ability to shape international norms and institutions according to its values. It may have put a premature end to the third wave of global democratization and let China write authoritarianism into the very code of emerging technologies in the early 21st century.

Relative to the cost of a power transition war and the opportunity cost of lost American hegemony, the projected cost of invading Iraq was negligible. The Brookings Institution’s Michael O’Hanlon predicted that a regime change war against Saddam would cause no more than 100 to 5,000 fatalities among U.S. and allied service members, and no more than 1,000 to 100,000 Iraqis, while saving countless Iraqi lives from Saddam’s tyranny. If a 21st century power transition war would have caused only as many deaths as World War II — which, mind you, was a mostly pre-nuclear war — then the invasion of Iraq only would have had to reduce the chance of a power transition war by between 0.0013% and 0.15% to be worth it in terms of lives saved in expectation. In other words, if there was a 1% chance that the Iraq War would have helped save American hegemony, then according to the estimates policymakers had access to at the time, invading Iraq could have been expected to save between 6.67 and 769 times as many lives as it would have ended. And as Dick Cheney put it, “[i]f there's a 1% chance [of a catastrophic outcome] we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response.”

These estimates are, of course, fantastical. Contemporary to the Iraq invasion, there was no reason to believe that failing to demonstrate U.S. power against any random country — Afghanistan excepted, of course — would have dealt any damage to the international order. To the contrary, even mainstream critics of the Iraq War, like the political scientist John Ikenberry, predicted that the Bush administration’s “neoimperial” foreign policy would undermine the basic sovereignty norms and multilateral institutions that had helped maintain the groundwork for international peace and prosperity since World War II.

In fact, the steelman case for invading Iraq is so shot through with analytical errors that it’s hard to believe so many members of the expert class accepted it at the time.10 For example:

It fixes the meaning of 9/11 as the opening shot of a civilizational war between Islam and the West rather than a tragic one-off security failure or the predictable result of two decades of military intervention in the Muslim world.

It conflates the insecurity of U.S. policymakers trained to think in terms of threats and weaknesses with the ambitions of largely defensive realist foreign powers mostly satisfied with the international status quo.

It ignores the unprecedented outpouring of international good will for the United States in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. This includes substantial cooperation in the so-called “war on terrorism” by ostensible U.S. adversaries in Libya, Syria, China, and Russia.11 Iranian leaders, including the Ayatollah Khamenei, denounced the attack and allowed a pro-American candlelight vigil to proceed in Tehran. Saddam Hussein personally expressed his sympathies via email to an American computer engineer who contacted him in October 2001.

It assumes that deterrence is reputational even though evidence suggests it’s the product of case-specific circumstances.

It concludes that going to war on a lark inevitably makes the United States look strong, and not reckless or irrational, and doesn’t raise any alarm bells in foreign capitals or provoke a defensive response from states that fear they might be next.

The most reasonable explanation for the triumph of the Ledeen Doctrine in Iraq is that U.S. foreign policy elites simply couldn’t take the perspective of other states’ strategic decisionmakers. If they had, they would have understood that complacency toward Saddam was always an acceptable option, but invading Iraq would have generated untold dissatisfaction with the international order. To maintain that other countries harbor literally unlimited desires and a canny sixth sense for American weakness, but for some reason passively accept American hyperpower, requires a lot of projection and a lot of wishful thinking.

A corollary to this explanation is that the United States invaded Iraq in order to improve its self-esteem. The international community apparently did not believe the United States was any less powerful on 9/12 than it was on 9/10. But to a domestic audience — especially those who believed the United States had spent the last decade lost in the woods, serendipitously unaware of the acute and chronic threats posed by rogue states and great power competitors — the 9/11 attacks were foremostly a humiliating event that demanded long-overdue retribution. The United States needed to pick up some small crappy little country and throw it against the wall, not to show the world we mean business, but to make ourselves feel better.

Comedian George Carlin called this the “Bigger Dick Foreign Policy Theory.” Its central premise is as follows: “What, they have bigger dicks? Bomb them!” It was first posited to explain the Persian Gulf War as part of Carlin’s show Jammin’ in New York in 1992, but it works verbatim for the Iraq invasion a decade later:

In this particular case, Saddam Hussein had challenged and questioned the size of George Bush’s dick. And George Bush had been called a wimp for so long — “wimp” rhymes with “limp” — that he had to act out his manhood fantasies by sending other people’s children to die. Even the name “Bush” is related to the genitals without actually being the genitals. A bush is a sort of passive, secondary sex characteristic. Now, if this man’s name had been George Boner, well, he might have felt a little better about himself and we wouldn’t have had any trouble over there in the first place.

Carlin is basically right, only the president doesn’t have so much autonomy. Maybe in a communist country like Sweden they go to war whenever the president feels bad about himself, but here in America we do things a little differently. We only do our performative wars when the whole country is trapped in some Freudian funk and we need to blow some people’s limbs off to get out of it. And of course, the number of people whose limbs we need to blow off is proportional to the depth of the funk.

After Vietnam, America was stuck in some deep psychological doo-doo. Norman Podhoretz — a neoconservative intellectual whom the libertarian economist Murray Rothbard once compared to a Joseph Heller character “whose sole literary output is a series of autobiographies celebrating his own life and thought” — complained that the Vietnam Syndrome had rendered even the likes of Henry Kissinger and Gerald Ford into isolationist surrender monkeys. Reagan and Bush tried to pull America out of its funk by bombing a hospital in Grenada and blasting Guns N’ Roses at the CIA’s old friend Manuel Noriega’s hideout in Panama, but it took a right proper war with a right proper social mobilization — slick Kuwaiti propaganda, round-the-clock TV coverage, Whitney Houston belting the national anthem at the Super Bowl, etc. — to finally do the trick.12 According to the political scientist John Mueller, the broad-based destruction of the bombing in Iraq, compounded by sanctions after the war, killed more people than chemical, biological, and atomic weapons had killed in all of human history. And Poppy’s approval rating climbed up to 89%.

So, too, was America in some doo-doo after 9/11 — see above for the evidence.13 This was temporarily resolved by the second Iraq War. All the enemies of freedom worldwide, from Phil Donahue to the Dixie Chicks, got their comeuppance.14 “The Right Brothers,” a pro-war conservative rock duo from Nashville, won widespread acclaim for their 2005 single, “Bush Was Right.” It declared, not in so many words, that the Ledeen Doctrine had succeeded —

Democracy is on the way, hitting like a tidal wave

All over the Middle East, dictators walk with shaky knees

Don’t know what they’re gonna do

Their worst nightmare is coming true

They fear the domino effect, they’re all wondering who’s next

— and America was back, baby. Meanwhile, the opposition leader of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, a 60-year-old whippersnapper by the name of Joe Biden, told the Brookings Institution that his harshest criticism of the administration was that the president hadn’t leveled with the American people and said: “We have to finish the job.”

There were 12 years between the first Iraq war and the second. It’s been 13 years since the second one officially ended, and Americans are getting antsy again. The current era of bad feelings unofficially began when the United States “pulled out” of Afghanistan in August 2021 (note: the phallic double entendre) and the honeymoon period closed on the Biden administration. The New York Times lamented on its front page: “U.S. Afghan Departure Strikes Another Blow To American Credibility.” The Republican chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Michael McCaul, bombasted from before America left, until the very end of the Biden administration, that the decision to “suddenly” get out of Afghanistan — after 7 years of hemming and hawing — had emboldened China, Russia, and Iran, and “lit the world on fire.” The last time more than one-third of Americans told pollsters they believe the country was headed in the right direction was on August 22, 2021 — a week after the fall of Kabul.

Biden and his national security team spent about three years trying to shake off America’s loser stink, but nothing they did ever quite worked. A hundred billion dollars in aid to Ukraine did little more than prolong the war and spark a contest of resolve with Vladimir Putin. Meanwhile, the sanctions — whose worst effects Russia managed to avoid, anyway — helped drive gas prices up to five dollars a gallon.15 The once tried-and-true method of blowing up brown people in the desert didn’t seem to work this time, for whatever reason. And the embarrassment was compounded when it put the kibosh on Biden’s inexplicable efforts to broker a Saudi-Israeli deal and provoked a bunch of khat-chewing fanatics near the Bab el-Mandeb into launching a wholesale assault on the global shipping industry. By the end of his term, Biden’s job approval on foreign policy was 25 points underwater and he was considering a lame-duck strike on Iran just to have something to put next to his name in the history books.

America’s ongoing crisis of confidence is among the most dangerous trends in the world today. It wasn’t enough to push the Biden administration into a Ledeenian-style war for self-esteem (unless you count the proxy wars) but that’s just because Biden had a modicum of practicality left in his rapidly diminishing mind. Not so for his successor. Foreign policy experts fear that when Xi Jinping talks about Chinese “national rejuvenation,” it’s a euphemism for international belligerence and territorial expansion. They should be at least as concerned — and probably much more — about Trump’s so-called American “Golden Age.” In his inaugural address, Trump threatened to steal the Panama Canal and expand American territory, “to once again act with courage, vigor, and the vitality of history’s greatest civilization.” He constantly talks about annexing Canada and invading Greenland as projects of national renewal. During his first week in office, he threatened tariffs and sanctions against Canada, Mexico, Denmark, Russia, China, Colombia, and the European Union for crossing the United States.

Then there are his advisors: Pete Hegseth likens himself to a crusader. Mike Waltz — once an advisor to Dick Cheney — advocated a 100-year war in Afghanistan framed as a civilizational battle between good and evil. When Marco Rubio, America’s new top diplomat, ran for president in 2016, he lifted his campaign slogan, “A New American Century,” from the name of the neoconservative think tank, the Project for the New American Century, that served as a government-in-waiting for the George W. Bush administration and helped lay the blueprints for the Iraq War.16 At his confirmation hearing, Rubio asserted that the “post-war global order” — supposedly defined by the usurpation of American national interests to a rootless cosmopolitanism — is not only “obsolete,” but a “weapon” being employed against the United States by bad actors like China and Iran.

Let us grant this conspiracy of über-nationalist boobs an undeserved benefit of the doubt: say they don’t consciously want a war. How else is this supposed to end? Since 1945, the peace has been kept by American economic and military preponderance — ironically sustained by the United States restraining itself to avoid provoking allies and adversaries into militarization — unprecedented commercial globalization, norms of territorial integrity, and mutually assured destruction. The Trump regime promises to undermine every one of these pillars. You cannot remain preponderant by estranging your allies while antagonizing your enemies. You cannot maintain globalization by further weaponizing the international trade and financial system. You cannot uphold international norms by trampling them with impunity. You cannot preserve the balance of terror and pursue nationwide missile defense at the same time.

A deceptive alternative is to attempt to remain aloof of great power conflict and instead pursue a “splendid little war” in the Western hemisphere or a good, hard thrashing of the Iranians in retaliation for their never having thanked us for getting half a million of them killed in the 1980s. If not Panama or Greenland, Rubio surely has a list of targets he’d like to strike in Cuba, Venezuela, and any other paisito de mierda with a leftist president. Waltz wants to go for Mexico. Trump says: “Stranger things have happened.” The Wall Street Journal reports the president is “weighing options” to bomb Iran. During his first administration, he toyed with the idea as late as two weeks before leaving office.

But a feel-good strike against a crappy little country is also a strike against the pillars of international peace. There are not enough carrots and sticks in the world to make it go down easy with allies or adversaries. Maybe you could buy off some votes in the U.N. General Assembly, but that’s about it. The Chinese get the moral high ground, and it becomes a lot harder to stop them from taking Taiwan.17 Meanwhile, the Russkies, having just gone through their own Afghanistan (not to be confused with their other own Afghanistan) might see fit to give us our own Ukraine — at which point, the sky’s the limit on the escalation ladder.

Something has to give: either the Long Peace or the Long March for American Greatness. It feels hyperbolic and even anachronistic to be talking about the possibility of great power war, but that’s the point we’re at. The American people got in a funk, and they chose the Insane Clown Posse to help cheer themselves up. This isn’t like the first Trump administration, which kept some semi-competent experts around who slow-walked or shot down the president’s worst ideas, and didn’t have four years ahead of time to cook up a revisionist fever dream. This isn’t even like the Bush administration, which wanted — but didn’t know they would have the opportunity — to rough up some international miscreants, until the day the opportunity arrived.

We are still a nation of bad vibes, however. Someone needs to reckon with it, and hopefully it won’t be ourselves. If crappy little wars are a once-a-decade phenomenon, then it seems we’re overdue.

This Kennedy article — titled “The Eagle Has Landed” and published by the Financial Times in 2002 — is widely quoted and cited across the literature on unipolarity, but I’ve never actually tracked down the primary source. This particular quote is drawn from G. John Ikenberry, Michael Mastanduno, and William C. Wohlforth, “Unipolarity, State Behavior, and Systemic Consequences,” World Politics 61, no. 1 (January 2009): 10.

Christopher Layne, “The Unipolar Illusion: Why New Great Powers Will Rise,” International Security 17, no. 4 (Spring 1993): 17.

Ronald R. Krebs, Narrative and the Making of US National Security (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 149.

Richard Ned Lebow, A Cultural Theory of International Relations (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 473.

Quoted in Stephen Glain, State vs. Defense: The Battle to Define America’s Empire (New York: Random House, 2012), 379.

Michael R. Gordon and Bernard E. Trainor, Cobra II: The Inside Story of the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq (New York: Random House, 2006), 11.

Ibid.

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks on the United States, The 9/11 Commission Report, 22 July 2004, 559.

Graham Allison, Nuclear Terrorism: The Ultimate Preventable Catastrophe (New York: Times Books, 2004), 15.

Actually, it’s not very hard to believe. See my article, “Foreign Policy Elites Fail Upwards,” about some of the ridiculous things taken for granted by the U.S. foreign policy establishment.

Libya and Syria covertly received many terror suspects from the United States with the implicit understanding that they would be tortured. A Human Rights Watch report based on recovered documents and interviews conducted after the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 found that the United States not only delivered Gaddafi’s enemies to Tripoli, “but it seems the CIA tortured many of them first.” A former CIA case officer, Bob Baer, remarked to the New Statesman in 2004: “If you want a serious interrogation, you send a prisoner to Jordan. If you want them to be tortured, you send them to Syria.”

The United States also cooperated with China, detaining 22 Uyghur Muslims suspects at the Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp at China’s behest between 2002 and 2013. Most of these suspects were never charged with a crime. The Justice Department found in a 2008 investigation that U.S. interrogators “appeared to have collaborated with visiting Chinese officials at Guantánamo Bay to disrupt the sleep of Chinese Uighur detainees, waking them every 15 minutes the night before their interviews by the Chinese.” A U.S. Senate report, also published in 2008, found that many of the interrogation techniques used at Gitmo, including sleep deprivation, were lifted from a 1957 Air Force study describing torture practices used by members of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army against American soldiers in the Korean War.

A particularly amusing anecdote from philosopher Paul Patton’s introduction to Jean Baudrillard’s volume The Gulf War Did Not Take Place:

At the time, the TV Gulf War must have seemed to many viewers a perfect Baudrillardian simulacrum, a hyperreal scenario in which events lose their identity and signifiers fade into one another. […] Occasionally, the absurdity of the media’s self representation as purveyor of reality and immediacy broke through, in moments such as those when the CNN cameras crossed live to a group of reporters assembled somewhere in the Gulf, only to have them confess that they were also sitting around watching CNN in order to find out what was happening. Television news coverage appeared to have finally caught up with the logic of simulation.

It seems worth noting that the 9/11 attacks possibly never would have occurred if the United States hadn’t gone to war with Saddam in 1990–91 or had conducted itself more prudently in the war’s aftermath. Osama bin Laden’s 1996 and 1998 fatwas mentioned three overriding motivations for attacking the United States. These were that the United States maintained military bases in Saudi Arabia from which it enforced its Iraqi no-fly-zones, it starved hundreds of thousands of Iraqi children through its sanctions regime against Saddam, and it supported Israel. These themes were also the basis of most of al-Qaeda’s Arabic-language propaganda: even if they were a cynical fig leaf for bin Laden’s real motivation of Hating Our Freedoms — and there’s no evidence of that — they were apparently genuine for the bulk of his supporters who committed jihadist violence. As political scientist Robert Pape found in his groundbreaking study of the motivations of suicide terrorism:

Most suicide terrorism is undertaken as a strategic effort directed toward achieving particular political goals; it is not simply the product of irrational individuals or an expression of fanatical hatreds. The main purpose of suicide terrorism is to use the threat of punishment to coerce a target government to change policy, especially to cause democratic states to withdraw forces from territory terrorists view as their homeland.

Donahue’s talk show was cancelled by MSNBC on February 25, 2003, supposedly due to low ratings. However, Donahue’s ratings were the highest of any program on the network at the time. A leaked NBC internal memo stated that Donahue would be a “difficult public face for NBC in a time of war […] He seems to delight in presenting guests who are anti-war, anti-Bush and skeptical of the administration’s motives,” and expressed fear that Donahue’s show would become “a home for the liberal anti-war agenda at the same time that our competitors are waving the flag at every opportunity.”

Donahue was replaced by pro-war conservative shock jock Michael Savage, whose show was described by MSNBC president Erik Sorenson as “destination television for those looking for compelling opinion and analysis with an edge.” By July 2003, Savage was fired for saying to an on-air caller: “Oh, you’re one of the sodomites. You should only get AIDS and die, you pig. How’s that? Why don’t you see if you can sue me, you pig. You got nothing better than to put me down, you piece of garbage. You have got nothing to do today, go eat a sausage and choke on it. Get trichinosis.”

I don’t drive, so this means nothing to me. If anything, I think gas should be even more expensive because climate change is plausibly the worst thing ever. But I understand that most people don’t like it and it’s often a good proxy for national self-esteem.

Rubio’s national security team during his 2016 campaign also included PNAC members Elliott Abrams, Eliot Cohen, Paula Dobriansky, Aaron Friedberg, and Dov Zakheim.

Recent research on whataboutism and U.S. public opinion finds that Americans are significantly less likely to support sanctions against foreign actors for behavior that they’re informed the United States participates in as well. Among other results, 67% of Americans supported sanctions against Russia when told that Russia had interfered in a democratic election or violated the rights of refugees. But only 55% continued to support sanctions after shown a mock statement from a Russian spokesperson pointing to recent and similar U.S. election interference or mistreatment of migrants.

Although I am loath to cite the bumbling Thomas Friedman, the following quote from a recent column is instructive:

Question: “What does Xi Jinping feel when Trump starts talking about taking Greenland and the Panama Canal?”

Answer: “Hungry” — for Taiwan.

You should tag all the big names you mention in your articles — Caplan, Yglesias, etc. They might find your blog and promote it!

The Brookings Institution has deposited $600 into your account