I recently turned on paid subscriptions for the newsletter. Articles this long will typically be paywalled, so if you like it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. In addition to all paywalled content, you’ll gain access to the subscriber chat on the Substack app, where you can request articles and podcast episodes about topics of your choice, and I’ll link to occasional article drafts and monthly paid-subscriber-only video calls. It’s just $5 per month, and unlike the U.S. foreign policy establishment, you can unsubscribe from it at any time.

Some time ago, a reader shared an old Scott Alexander post, “Military Strikes Are An Extremely Cheap Way To Help Foreigners,” in an attempt to convince me — you guessed it — that military strikes are an extremely cheap way to help foreigners.

Reading the post, I had two reactions.

First was that military strikes are, in fact, an extremely expensive way to help foreigners.

Second was that even an incredibly smart person like Scott is liable to get things wrong in a domain where he’s not a subject matter expert, like foreign policy. This is worse still when the field’s real experts all systematically fail upward.

Scott’s argument is that if you take the cost of the 2011 regime change in Libya and divide it by the estimated number of lives saved by the intervention (he says 25,000), plus the improvement in quality of life for everybody else in the country, you get an estimated cost of $65 per QALY, or less than the cost of GiveWell’s top charities and less than 1% of the cost of other well-regarded international health charities. This doesn’t mean that every military intervention is always worthwhile, since they sometimes kill a lot of people, cost a lot of money, don’t succeed, or risk unintended consequences. But it suggests that military action can sometimes be a good way to help people abroad.

At the time Scott wrote the piece in 2013, this was widely regarded as the reasonable thing to believe. In early 2012, the U.S. permanent representative to NATO Ivo Daalder and the head of the U.S. European Command and NATO’s highest-ranking military official James Stavridis boasted in Foreign Affairs that:

By any measure, NATO succeeded in Libya. It saved tens of thousands of lives from almost certain destruction. It conducted an air campaign of unparalleled precision, which, although not perfect, greatly minimized collateral damage. It enabled the Libyan opposition to overthrow one of the world’s longest-ruling dictators. And it accomplished all of this without a single allied casualty and at a cost — $1.1 billion for the United States and several billion dollars overall — that was a fraction of that spent on previous interventions in the Balkans, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Even after the September 11, 2012, terrorist attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, this remained the mainstream consensus. One representative commentator, Chris Chivvis of the RAND Corporation, declared that the existence of a power vacuum in Libya and the increasing presence of al-Qaeda in the country “did not change the fact that the intervention had toppled Muammar Gadhafi and opened the door to a better future,” nor that the operation “was a genuine if moderate success” that saved a large number of civilian lives.

Only after Libya had descended into civil war in 2014 did it become mainstream to admit the intervention was a failure: No, it was not clear that Gaddafi was about to commit Rwandan-style mass violence against his political opponents; and no, it was not the case that the intervention had saved “tens of thousands of lives,” as per Daalder and Stavridis, or “hundreds, perhaps thousands” per Chivvis. To the contrary, contemporaneous reports by human rights observers suggest that the Libyan government typically avoided using indiscriminate force against nonviolent civilians. In Misrata, the most intense theater of the war, just 3% of the wounded were women and children, far from the more than 50% you would expect if the government was using force indiscriminately.1

Political scientist Alan J. Kuperman suggested in the scholarly journal International Security in July 2013 (two months before Scott’s article, although he wasn’t published in the more establishmentarian Foreign Affairs until early 2015) that if NATO had not intervened, Libya’s civil war likely would have ended within weeks and with few more than 1,100 fatalities. This is because Gaddafi’s forces had been quickly retaking Libya’s largest cities with limited fatalities on any side, and by mid-March 2011 most rebels were either fleeing to Egypt or laying down their arms. Although it was widely reported in the international press that Gaddafi was planning to commit a massacre in Benghazi, Kuperman notes that such a move would have been unusual as Gaddafi had not done anything similar in the other cities he retook from the rebels. In fact, Gaddafi’s supposed “genocidal rhetoric” about “clean[ing]” Libya of its “dirt and impurities” and exterminating “cockroaches” and “rats,” was, in context, explicitly directed toward armed rebels and excluded civilians and opposition fighters who fled the country or surrendered.

(And in case you think this Kuperman fellow is just a tankie, here’s an op-ed he wrote in the New York Times calling for the United States to bomb Iran.)

After the United States first intervened on behalf of the rebels, the war lasted another seven months and some 8,000 Libyans were killed. Following Gaddafi’s ouster, the NATO-backed rebels summarily executed dozens of former regime loyalists and unleashed a reign of terror against black Libyans and African guest workers. Salafi jihadists pilfered weapons from the former regime and trafficked them to conflict zones across the region. Some joined the insurrection in Mali on behalf of Islamist terror groups and ethnic separatists and contributed to the destabilization of one of North Africa’s strongest democracies. President Obama admitted in 2016 that failing to plan for the day after Gaddafi fell was the “worst mistake” of his presidency.

Ex post, it is clear that the Libyan intervention was not an extremely cheap way to help foreigners. This is primarily because it did not actually help foreigners, but also because in order to have helped foreigners, it would have required a costly and indefinite deployment of U.S. troops to fight Islamist militants and rebuild the country’s political institutions. If the occupation of Libya would have cost just half as much as the war in Afghanistan and produced the same putative benefit that Scott supposed it would, the cost per QALY would have been around $75,000, or a thousand times as much as the top GiveWell charities.

That the Libyan intervention was not going to help Libyans should have been clear ex ante as well. The information cited above about the threat to civilians posed by the Gaddafi regime was all available during the debate over the U.N. Security Council Resolution to authorize a protective mission. So too was intelligence about the violent jihadist nature of the opposition. So too about the balance of power. If a war ends when the relevant parties agree on the basic question of who will rule — either because they have negotiated for it, or one side has been cowed into submission — then an intervention that favors the weaker side in a conflict will inevitably extend the length of the war and get more people killed than an intervention on behalf of the strong.

Yet, if the failure of the Libyan intervention was so obvious, why did a smart person like Scott not realize it?

My first thought is that Scott just isn’t an expert on foreign policy, so it’s rational for him to defer to the expert consensus on the Libyan intervention. Most people don’t have the background knowledge or patience to assess, say, what threat Gaddafi posed to the opposition in Benghazi, so it saves time to trust the people who ostensibly should know better.

But this doesn’t tell us why both Scott and the experts got Libya so wrong. It is generally a good heuristic to trust the experts in any given field because they are usually selected for their deft analysis and competent decisionmaking. This is true to an extent of the national security elite; you are unlikely to succeed as a think tank wordcel or government analyst unless you have some base level of intelligence and familiarity with your domain (Doug Feith, “the fucking stupidest guy on the face of the earth,” excepted). Yet, foreign policy professionals almost never face consequences for getting important things — like the fates of nations and thousands of people’s lives — utterly and terribly wrong.2 Why so?

The general answer is that the members of the U.S. national security elite are selected for their groupthink and adherence to a grand strategic vision of American primacy. As Chris Layne and Pat Porter show, the United States has adhered to a primacist foreign policy uninterrupted since at least 1945, and this has produced a perverse elite ideology that regards the ideas underpinning primacy as axiomatic and beyond reproach. The gatekeeping institutions of the national security state therefore systemically — even if not deliberately — promote adherents and punish and purge dissidents to the primacist consensus no matter the outcomes it produces. As then-president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, Leslie Gelb, stated in 2009, the reason that he and many others initially supported the Iraq War (which he admitted was “symptomatic of unfortunate tendencies within the foreign policy community”) was that they had succumbed to “the disposition and incentives to support wars to retain political and professional credibility.”

The specific answer for why foreign policy elites got Libya wrong is at least three-fold. First, policymakers since at least World War II have internalized a script and mental schema that frames the United States and its allies as inherently moral and its adversaries as unmitigatedly evil, a dichotomy that predisposes them to misinterpret or invent evidence as confirmation of an enemy’s malevolence and an enemy’s enemy’s virtue.

Similar to Saddam Hussein, some American policymakers regarded Gaddafi as a cartoonishly evil despot and a New Hitler who, if allowed to remain in power, would resort to any dark deed to crush the opposition. Western media credulously repeated a Libyan opposition leader’s assertion that if Gaddafi took Benghazi, his forces would kill half a million people, or hundreds of times as many as had been killed in the entire war up to that point. President Obama and his State Department’s former Director of Policy Planning Anne-Marie Slaughter publicly invoked the Rwandan genocide as justification for intervening. The administration’s ambassador to the United Nations, Susan Rice, told the U.N. Security Council in April 2011 that Gaddafi was supplying his troops with Viagra to encourage them to commit mass rape. In fact, U.S. intelligence officials at the time said they had no information to support the claim, and both Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch shortly thereafter failed to find any evidence that Libyan forces were using rape as a weapon of war, not even “a single victim of rape or a doctor who knew about somebody being raped.”3

Officials meanwhile dismissed or ignored evidence that many of the Libyan rebels maintained ties to militant jihadist groups that were largely responsible for instigating violence. Even though it was well known that some elements of the opposition were linked to al-Qaeda, including a former commander of the U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, it apparently did not strike the Obama administration as urgent to engage in any postwar planning to prevent a jihadist insurgency. Senator John McCain, who visited Benghazi a month after the intervention began and met with armed rebels, declared that they were “[his] heroes” and “not al-Qaeda,” but “brave fighters [and] Libyan patriots.”4 Senator Marco Rubio, now likely the next secretary of state,5 remarked on another trip that:

We’re very happy to see the pro-American enthusiasm that we encountered. And we have hope for Libya’s future. Five years from now, three years from now, we could have a nation in the northern part of Africa that is Islamic and Arab, and yet pro-American and a democracy. And our ally in confronting the problems of the region and the world. That’s the opportunity before us.

(Three years after Rubio said this, Libya was mired in a civil war. Five years after, it was home to as many as 6,500 ISIS fighters.)

A second reason that foreign policy elites got Libya wrong is that they are, in general, overconfident in the power of military force put to political ends. Libya was supposed to be a triumph for the doctrines of responsibility to protect (R2P) and humanitarian intervention, which hold that the international community has a duty to intervene — sometimes militarily — to prevent mass atrocity crimes when governments are either unable or unwilling to protect their populations. Although U.N. Security Council Resolution 1973 merely authorized a mission to protect Libyan civilians, the United States always intended to go a step further and from the beginning sought to topple the government and effect a transition to more liberal rule. Moreover, it sought to do so with minimal investment by itself, hence the operation cost the United States just $1 billion, or the equivalent of three days of the war in Afghanistan, and involved minimal American boots on the ground and no casualties. Hillary Clinton called the operation “smart power at its best.”

But the light footprint strategy failed. Libya held one democratic election in 2012, then broke into civil war and a third of the country was taken over by a warlord and accused torturer, while the internationally recognized government also committed widespread and systematic crimes against humanity. Things were so bad under so-called “democracy” that the first national survey of Libya, conducted two months after Gaddafi’s removal, found that a plurality of people actually wished they could return to dictatorship:

People prefer a single or a group of leaders over democratic models. In 12 months time 42% say they want a strong man (or men) while, in fourth position, only 15% favour a form of democracy. In second position is a technocratic government (21%), and the [National Transitional Council] in third (17); though the NTC will not go on beyond June 2012. In 5 years’ time, the democratic models improve from 15 to 29%, but autocracy/oligarchy are still in the lead at 35%.

If the foreign policy establishment rewarded competence, American policymakers would have learned long before 2011 that you can’t simply remove a regime, or re-engineer a society to embrace liberal democracy, and expect to do it without incurring significant costs or promoting instability. After 9/11, the United States and its Afghan partners defeated the Taliban in just over two months with minimal ground forces or casualties and a price tag of just $3.8 billion. By 2011, however, the United States was forced to maintain a footprint of nearly 100,000 troops in Afghanistan to maintain stability, at a cost of more than $100 billion per year, while the U.S.-backed government remained plagued by corruption and insurgents launched more than 1,500 attacks per month. In Iraq, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld predicted that the United States would spend no more than $50 billion over the length of the war. By 2011, it had spent nearly $800 billion and suffered more than 4,500 fatalities. Rumsfeld’s philosophy, as one ex-policymaker put it, “that the U.S. can invade a country, overthrow its government and escape responsibility for the consequences,” is widely recognized as having been a significant contributor to the breakdown of order in Iraq.

A third reason the experts got Libya wrong is that they overstate the salience of signaling credibility to allies and instilling fear in enemies. An Obama staffer famously described the administration’s approach as “leading from behind,” or allowing European NATO allies to conduct the majority of strike sorties and take credit for ousting Gaddafi even as the United States provided the lion’s share of non-combat support and effectively retained control over the operation. French president Nicolas Sarkozy (currently on trial for receiving illegal campaign funds from Gaddafi in 2007) was among the most aggressive advocates for regime change, becoming the first head of state to call for a no-fly zone in February 2011 and recognize the rebels as Libya’s legitimate government just weeks later.6 According to a 2016 British parliamentary inquiry, “the political momentum to propose [U.N. Security Council] Resolution 1973 began in France,” while British policy “followed decisions taken in France,” and the United States, in turn, followed France and Britain.

In the United States, the operation’s foremost champions — Daalder, Stavridis, and Chivvis — all credited the intervention with reinvigorating the NATO alliance by defining a new and enhanced role for European allies and setting a new standard for burden sharing. As Chivvis put it,

For the UK, France and NATO, success was thus evidence of their continued relevance and strength at a time when doubt about that relevance was strong. Europe’s protracted financial and economic crisis had forced deep cuts in already declining defence budgets. NATO was struggling to withdraw from Afghanistan with its integrity intact. Success in Libya demonstrated not only that NATO mattered, but also that the European Allies mattered within the Alliance.

With regard to the wider world, Chivvis added, the Libyan intervention ensured that the “wave of rebellion sweeping across the Middle East and North Africa [was not] slowed,” and served as an example to other repressive leaders like Syria’s Bashar al-Assad “to modify their strategies of political control in hope of avoiding Gadhafi’s fate.” French academic and diplomat Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer suggests that the intervention at least did not undermine, and at best breathed new life into, the doctrine of responsibility to protect. McCain and Rubio went him one further, declaring that the success of the revolution in Libya was inspiring for democratic reformers in China, Russia, Iran, Syria, and even Bahrain and Saudi Arabia.

Yet there was little reason to believe that the Libyan intervention would serve as a new model for humanitarian internationalism or multilateral cooperation, or set off democracy’s fourth wave. States typically do not assess other states’ credibility based on their track record of intervention, but the capabilities and interests that they have at stake in a particular theater. Therefore, engaging in peripheral interventions like the one in Libya may actually cast doubt on the United States’s commitment and ability to fulfill its core treaty obligations. Moreover, while France and Britain were the foremost agitators for conflict, the military operation was possible only because the United States refueled and resupplied its allies with munitions, a poor sign for European defense capabilities considering the tin-pot nature of the Gaddafi regime.

As for the Libyan intervention’s knock-on effects for global democracy, Kuperman suggests that international support for violent rebels in Libya may have predictably encouraged Syria’s peaceful protesters to take up arms, “[t]herefore, a significant portion of Syria’s death toll may be a consequence of NATO intervention in Libya.” Less obvious, but still important, NATO’s exceeding its mandate under Resolution 1973 likely undermined Russia, China, Brazil, and India’s trust in R2P and international institutions; the overthrow of Gaddafi after he embraced the West and gave up his nuclear program in 2003 reinforced North Korea’s aversion to disarmament; and out-migration from Libya following Gaddafi’s ouster contributed to the rise of the far-right in Italy.

The United States did not intervene in Libya because it had good reasons to believe that the intervention would be good for the people who lived there, nor because it had good reasons to believe that intervention was in the best interest of the American people; these are post hoc justifications at best. The intervention was driven by entrenched beliefs about America’s role in the world, underpinned by outdated and unquestioned assumptions about international politics. Foreign policy professionals are selected not for their analytical or decisionmaking skills, but their conformity to an elite ideology centered on American primacy and exceptionalism.

If you are not aware of this, it is rational that your priors might tell you the foreign policy experts probably enjoy access to some esoteric truth that is beyond the comprehension of mere plebeians. But when confronted with evidence to the contrary, you ought to update your beliefs accordingly. If the experts were chosen for their competence, they would not have intervened in Libya. They would not have expected the rebels to usher in a Jeffersonian democracy, they would not have attempted to demolish and rebuild a country’s social and political institutions on a budget of $1 billion, and they would not have believed that the decision whether or not to remove the junior partner of the Junior Axis of Evil would have had transformative implications for world order. If the experts were chosen for their competence, anyone who believed these things would have been laughed out of Washington.

Yet, nearly all the architects of the Libyan disaster have failed upwards. Hillary Clinton was nominated for president. James Stavridis was vetted to be her running mate. Susan Rice twice ended up under consideration for secretary of state, then made the shortlist to be Biden’s vice president, then landed a job at the White House. So did Samantha Power; Biden lauded her as “a world-renowned voice of conscience and moral clarity.” Ivo Daalder became president of a top-ranked think tank with a $13 million budget. John McCain was practically beatified by the liberal press. Marco Rubio became Trump’s nominee for secretary of state. Barack Obama went on to enjoy one of the most corrupt and lavish post-presidencies in modern American history. Meanwhile, thousands of Libyans are dead and their country is a failed state.

The ideology and personal and professional incentives to pursue a primacist foreign policy are so strong that there is little anyone can do to solve the crisis of groupthink in our elite national security institutions. Pat Porter suggests that:

For U.S. grand strategy to change, two developments would need to combine: rapidly changing material conditions, shocking enough to disconfirm the assumptions of the status quo, and determined agents of change willing to incur domestic costs to drive it. Absent these developments, Washington is likely to remain committed to primacy.

Unlike some advocates of a more restrained foreign policy, I do not believe that a rapid change in the distribution of power is imminently in the offing. Few have been better vindicated in recent years (in that very narrow sense) than Francis Fukuyama. However, the mere fact that our elites are more competent than the elites in backwater dictatorships does not mean that we should trust people who consistently — sometimes without fail — get important things utterly and terribly wrong.7

The obvious solution is to attempt to cultivate a meritocratic counterelite not beholden to groupthink and primacy. But this is easier said than done. Even the most competent critics of American foreign policy are often lazy and rely on habit rather than analysis to drive their policy recommendations. For example, John Mearsheimer — “that sole celebrity of international-relations theory” — only became so by systematically ignoring his intellectual forebear Kenneth Waltz’s admonishment against conflating IR and foreign policy analysis, and thereby treating complicated empirical questions like they can be answered by theory alone.

More importantly, there’s no obvious market for non- (let alone anti-) primacist foreign policy in Washington. The most prominent restrainer think tanks, the Quincy Institute and Defense Priorities (whether to still count Cato is a legitimate matter of debate), have tiny budgets and virtually no influence over the policymaking process. Progressives are totally shut out of the Biden administration’s foreign policy, and libertarians out of Trump’s. You can continue to deepen the bench of your restrainer shadow cabinet, but what difference does it make if no one ever hires them? As Van Jackson puts it, “The prospects for seeing the United States relate to the world in a more peaceful, egalitarian, and democratic way depend on the constraints of the political landscape.”8 And the constraints today — and for the foreseeable future — are narrow and unaccommodating.

The least that can be done is to attempt to delegitimize the so-called “experts” who have only ever failed upwards and left a long trail of bodies in their wake by either disregarding or embarrassing them. No, the Libyan intervention did not save 25,000 lives, and we shouldn’t assume that it did just because someone with a Ph.D. in laundering Qatari money from Johns Hopkins SAIS says so. In any other field, people who are wrong as badly and as often as U.S. foreign policy elites would find themselves living in a cardboard box under a bridge. But ideology is a helluva drug. It makes sovereigns out of knaves and subjects out of fools.

Do not be a fool. There are few domains where it is truly justified to ignore or disparage the experts who by wit and will have climbed to the top of their field. But this is one of them. If you would simply pass by the man under the bridge and pay him no mind, then pay no mind — or give a piece of yours — to the talking head, the State Department spokesman, and the think tanker. The difference between them is that the man under the bridge will not send your children to war.

Alan J. Kuperman, “A Model Humanitarian Intervention? Reassessing NATO’s Libya Campaign,” International Security 38, no. 1 (Summer 2013): 111.

Is it “almost never” or just never? I suppose you could say Hillary Clinton faced electoral consequences for supporting the Iraq War (see below), but she’s not exactly what I have in mind when I refer to “foreign policy professionals.”

You might also count the few people who have faced legal consequences for, say, failing to file the right paperwork, or committing some other technical misdemeanor while doing the same things that other members of the foreign policy elite do with impunity. Take the retired general, former President of the Brookings Institution, and one-time unregistered Qatari agent John Allen (who was investigated by the FBI but never charged). Again, this isn’t exactly what I mean when I say people don’t face consequences for “getting important things […] terribly wrong,” since these aren’t strictly policy issues.

By May 17, Rice’s fabrication had made its way to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno Ocampo, who compared the alleged use of Viagra by Libyan forces to the use of machetes by Hutu extremists in the Rwandan genocide:

There’s some information with Viagra. So, it’s like a machete. […] It’s new. Viagra is a tool of massive rape.

This was just two years after McCain had met with Gaddafi and promised to help Gaddafi’s son acquire U.S. weapons.

Notably, McCain had a similar relationship with the rebels in Syria, whom he said were also not infiltrated by extremists, but “freedom fighters” and “the right people we could get the right weapons to.” But as George Carlin put it, “If crime fighters fight crime and firefighters fight fire, then what do freedom fighters fight?” McCain never seemed to have gotten to that part.

Talk about failing upwards!

The following doesn’t have anything to do with Sarkozy, but I couldn’t find anywhere better to mention it.

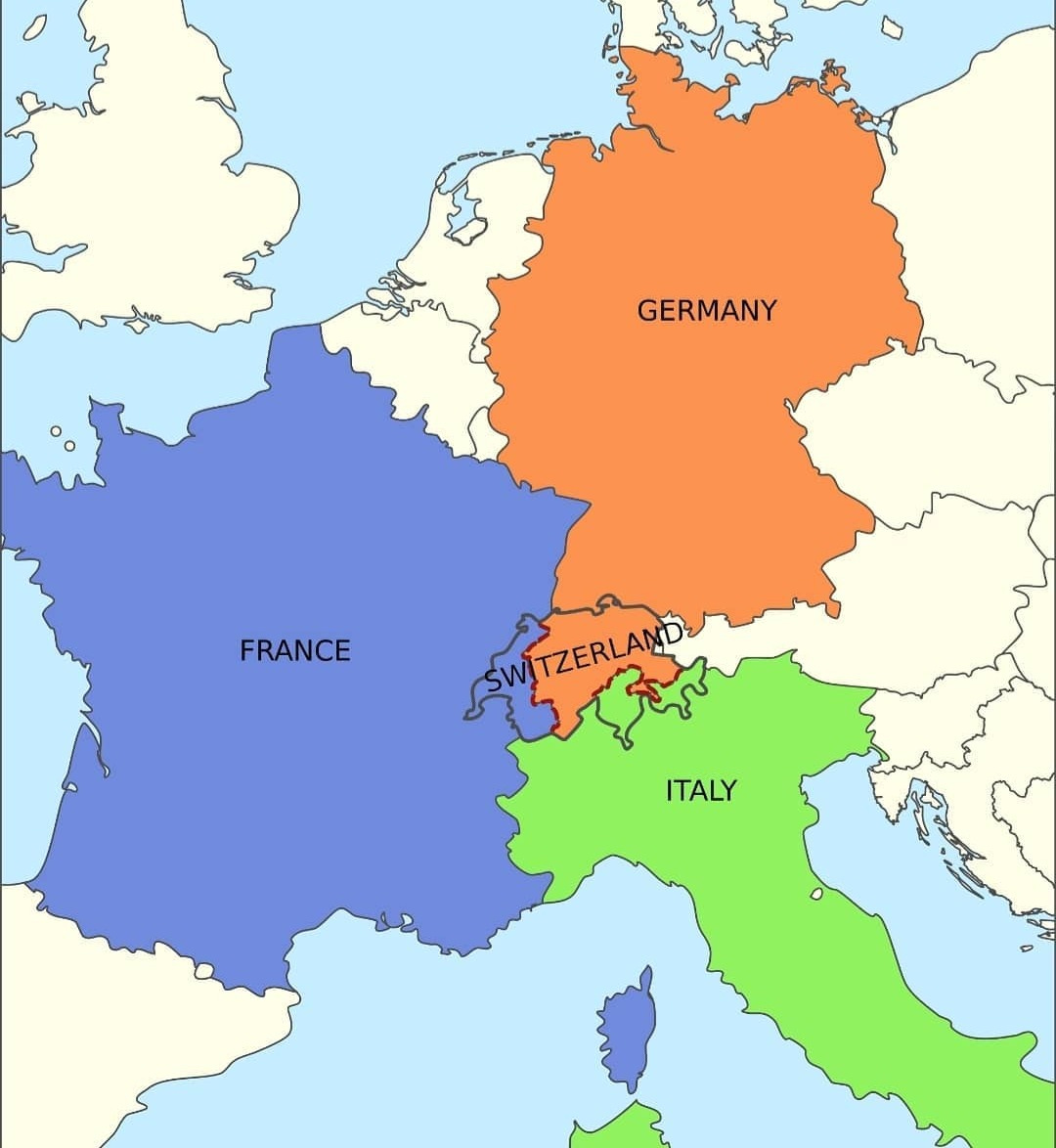

In July 2008, Gaddafi’s son Hannibal and his wife were arrested in Switzerland for allegedly beating their servants. Gaddafi retaliated by detaining two Swiss businessmen and imposing economic sanctions. In 2009, he submitted a proposal to the United Nations to abolish Switzerland and partition its territory between France, Germany, and Italy, calling Switzerland “a world mafia and not a state.” In 2010, he called for jihad against “unbelieving and apostate Switzerland […] by all means.”

For some reason, however, Gaddafi’s vendetta against Switzerland did not make it into his rambling, 95-minute speech to the U.N. General Assembly in 2009.

I am reminded of Matt Taibbi’s review of Thomas Friedman’s The World Is Flat:

Thomas Friedman does not get these things right even by accident. It’s not that he occasionally screws up and fails to make his metaphors and images agree. It’s that he always screws it up. He has an anti-ear, and it’s absolutely infallible; he is a Joyce or a Flaubert in reverse, incapable of rendering even the smallest details without genius. The difference between Friedman and an ordinary bad writer is that an ordinary bad writer will, say, call some businessman a shark and have him say some tired, uninspired piece of dialogue: Friedman will have him spout it. And that’s guaranteed, every single time. He never misses.

Van Jackson, Grand Strategies of the Left: The Foreign Policy of Progressive Worldmaking (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2024), 194.

I work in FP for a living, and this is the best thing I've read in weeks. Really patient, methodical, well-organized list of ways that "the blob" is consistently, predictably biased towards a romanticized vision of the U.S. military's role in the world, that just-so-happens to overlap with governments' innate temptation toward power aggrandizement.

I will add that I think both Cato and Chris Chivvis do good work that's aligned with the restraint movement today, however wrong Chris may have been about Libya a decade ago. Chivvis works in the same department of Carnegie that employs Stephen Wertheim, for example (whose book is another you should check out if you haven't already) and the two of them made similar points about the challenge of breaking from FP groupthink in a recent co-authored Foreign Affairs article. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/americas-foreign-policy-inertia

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=cBY-0n4esNY