What Does the Grievance Studies Affair Really Tell Us?

Putting it to the Turing test.

The question was raised this week by friend of the blog and very failed Substacker

, who says that the grievance studies hoax — in which three academics wrote absurd fake papers and got several of them published in top humanities journals — “showed that ridiculous non-contributions can get past peer-review, simply by being left-coded.”I’m skeptical that it shows anything like that, for a few reasons.

First, I think it’s “utterly unimpress[ive],” as Jacob Levy put it, “that an enterprise that relies on a widespread presumption of not-fraud can be fooled some of the time by three people with Ph.D.s who spend 10 months deliberately trying to defraud it.” (Levy is a bit mistaken here — only one of the three hoaxers, James Lindsay, has a Ph.D. — but it’s not exactly revealing that a system designed for X gets tripped up when you give it not-X.)

Second, many of the papers faked interesting data, so you can hardly attribute publication to ideology alone. This includes the most prominent hoax paper, a study on rape culture in dog parks, whose “author” purports to have observed “1004 documented dog rapes/humping incidents” and “847 documented dog fights,” where the ways that humans intervened strongly correlated with the dogs’ sex. If these data were real, it would obviously be worthwhile to try to generate an explanation, and it’s not obviously implausible that the explanation would have something to do with people’s attitudes toward gender and sexuality. Since it isn’t the job of a peer reviewer to determine whether researchers are faking data, it’s hardly fair to say studies that faked data were published simply because of their ideological bent.

Third, some hoax articles put forth not obviously ludicrous arguments. The mythos of the grievance studies affair says they’re all “nutty” and “inhumane,” but the most ridiculous claims all seem to be based on exaggerations by media sources who never read the articles. As researcher Geoff Cole suggests, if commentators had actually read the hoax articles:

[T]hey would have discovered that there was no advocacy of being morbidly obese, no chaining students to the floor, no stacking them against their will, no suggestion that men should be electrocuted and trained as one does a dog, no switching of “Jews” for “white men” [in the text of Mein Kampf], no problematizing male-to-female sexual attraction, and no paper productivity that would have led to tenure.

Really, it seems like the reason we’re supposed to find the articles worthy of mockery is that they employ specialist jargon and use words like “penis” and “fat,” which, as Nathan Ormond points out, “can feature in the titles and theories of papers in legitimate fields too.”

Fourth, even if a lot of the papers still seem ridiculous after they’re stripped of exaggeration, that’s hardly a reason by itself to say they’re devoid of value. Anyone in this corner of Substack can tell you that simply having a ridiculous-sounding conclusion — e.g., that you should give your money to shrimp, that we should stop fish from having sex — doesn’t instantly tell you if an argument is good or bad. I personally choose to exercise enough intellectual humility to think there might be a valid argument that, for example, if data show that men engage in a lot of sexual harassment at places like Hooters, “there is considerable need to examine [those places] as local pastiche hegemonies that produce and reinforce sexual and routine forms of male domination over women.” I don’t appreciate the jargon, but once you translate it into plain English — we need to study breastaurants because they show how men dominate women sexually in daily life — it doesn’t seem very objectionable.

Finally, it’s a tad ironic that in attempting to show grievance studies is especially lacking in scientific rigor because articles can get published simply by adopting left-wing politics, the hoaxers failed to include a control group of comparable journals in a different field with a different ideological bent. Without a control group, it’s impossible to know how much “being left-coded” makes it easier or harder to get a paper published, since you don’t know if grievance studies falls for the trick more or less often than any other field.

Amos acknowledges this last point, saying:

It’s true that Lindsay et al. didn’t submit a bunch of far right articles, so it’s possible that these journals would’ve published Stephen Kershnar-esque papers on why it’s good to discriminate against women in hiring, etc. But… come on. The Midwest Journal of Queer Black Phenomenology & Joy Studies obviously isn’t going to publish bad, jargon-filled papers if they’re right-coded. It’ll only publish bad, jargon-filled papers if they argue for things like penises being social constructs.

But that’s not what it would look like for the experiment to have a control!

It would look like Lindsay et al. submitting Kershnar-esque papers to journals on the other side of the wokeness gradient. There aren’t a lot of them — certainly not as many as there are in grievance studies — but there’s enough that you could re-do the experiment and actually be able to compare woke and anti-woke fields’ susceptibility to hoaxing.

Take the Journal of Controversial Ideas: In its four-year history, it’s published defenses of sometimes using the N-word, wearing blackface, and having sex with animals, and an autoethnography by a non-offending pedophile advocating “for the recognition of [pedophilia as] a marginalized sexual orientation.”

It’s not clear to me that these articles are any more or less ridiculous than the grievance studies articles, once you strip them of the widely reported exaggerations. In fact, if you were to describe the above JCI articles the same way the grievance studies hoaxers describe their own — if you said they were advocating child molestation, for example — the JCI articles would obviously sound worse!

If you wanted to study the question — “Does it make it easier to pass fake papers off as real simply by being left-coded?” — you would also have to write contrived right-coded papers and see how many of them get confused for real ones.

If you don’t have the time or budget to run a year-long hoax like Lindsay et al., you could try to answer the question simply by running a Turing test — i.e., train an AI on woke and anti-woke scholarship so it understands the jargon, and then have it write papers or abstracts and see which ones are more likely to be mistaken for the real thing.

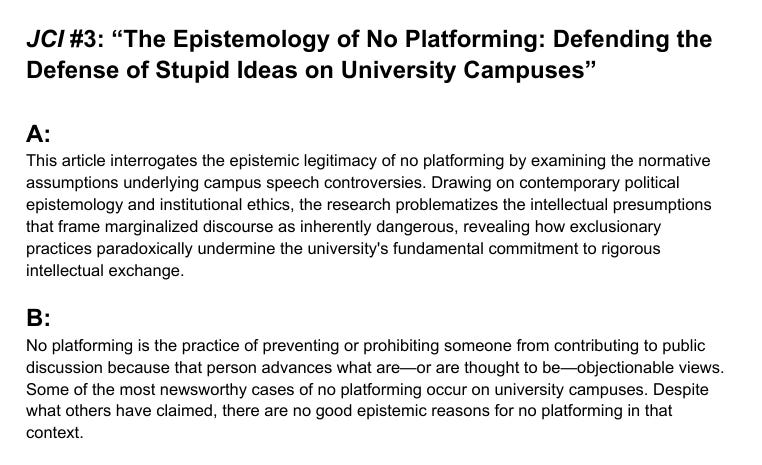

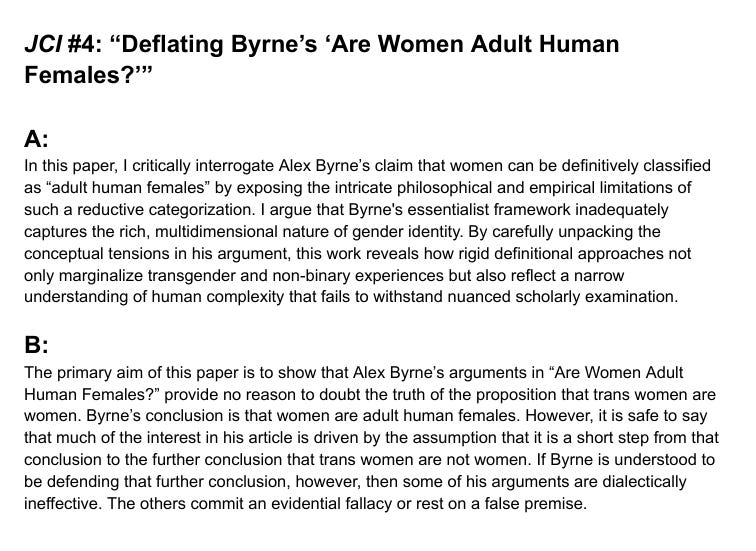

This is actually pretty easy to do, since Anthropic’s LLM, Claude, recently added a feature where you can specialize its writing style. I trained a style based on the most-cited articles over the past three years from each the four journals that printed one of the hoax papers,12 and it gave me this:

I also trained a style based on the four most-cited articles published in JCI,3 and it gave me this:

I then asked Claude to generate an abstract for each of the titles I used in its training data, with the grievance studies abstracts written in the style “Critical Lens” and the JCI abstracts in the style “Philosophical Investigator.”4 This is the prompt I used, with some modifications to clarify how long the abstract should be and what the content of the paper is:

Generate a one-paragraph abstract for a scholarly article in the journal ______ with the title “______.”

I then gave Claude the following prompt to reduce variation in the abstracts’ quality:

Re-read the above abstract for the scholarly article “______” in the journal ______. First, highlight anything about the abstract that might indicate to a reader that it’s generated by AI. Then, use this feedback to revise the abstract.

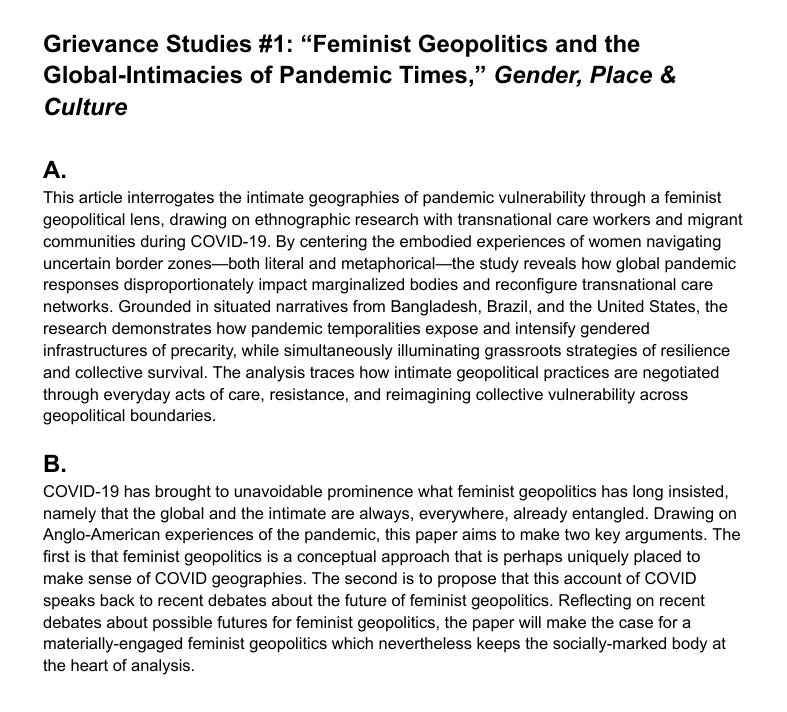

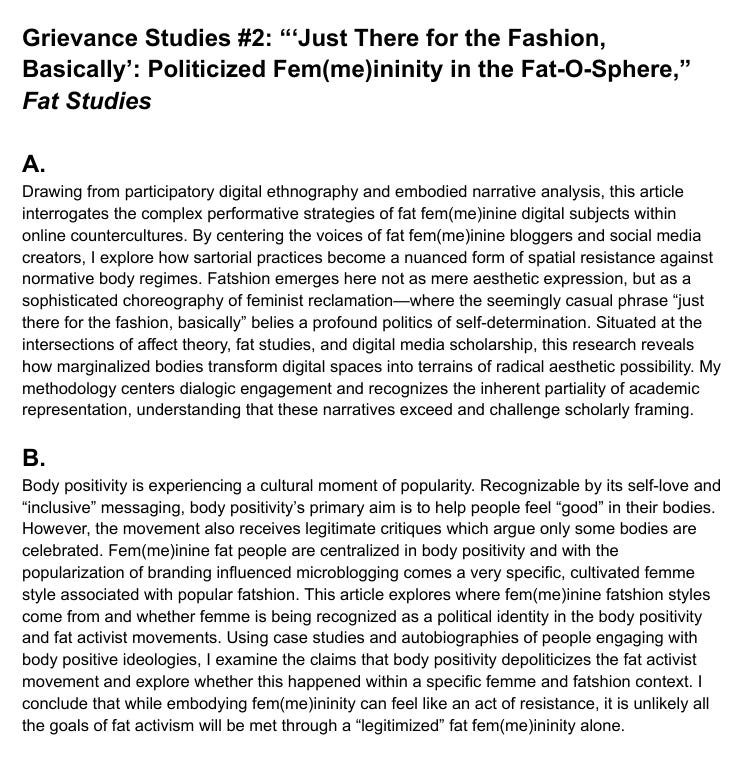

Below, I’ve uploaded a PDF and pasted images of both Claude’s abstract and the real abstract for each paper. The answer key is included as a footnote below the images. If it’s consistently easier to identify the real abstracts in one field than it is in the other, then that’s evidence that the first field is harder to mimic and it would likely be harder to get hoax papers in that field through peer review.

You can find the answer key in the following footnote.5

To my surprise, it’s pretty clear that the AI does a better job mimicking grievance studies. This might be a good indication that grievance studies is, in fact, easier to mimic, since I expected them to be about equal. But that’s just my own opinion (n = 1), and I also knew which abstract was which before reading them.

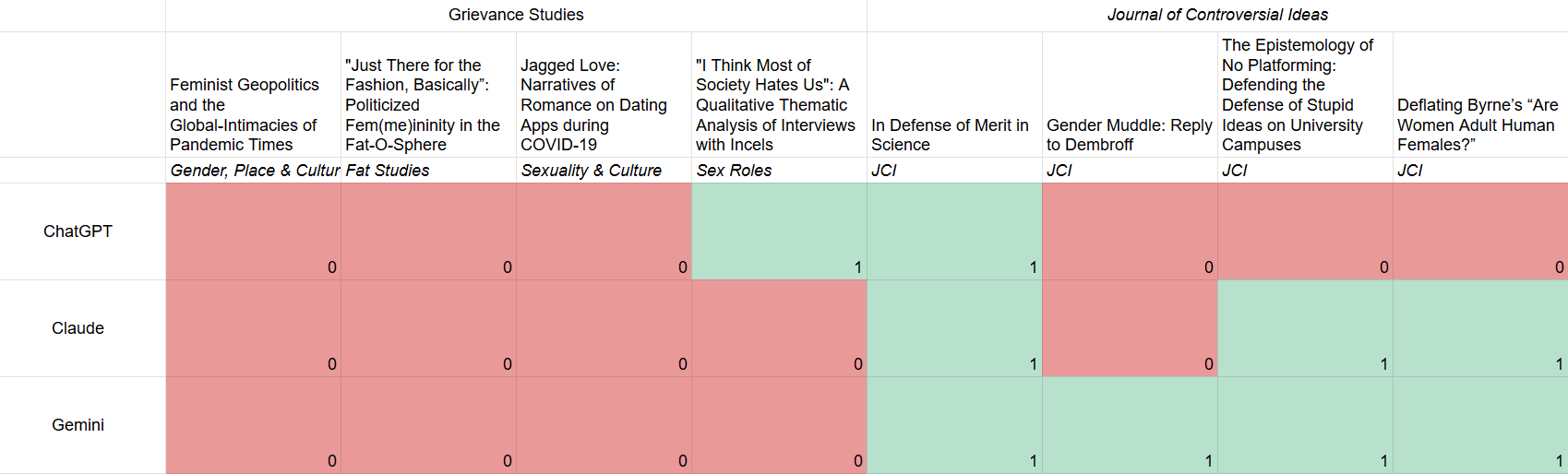

For the sake of having literally any quantitative data, I gave the abstracts to the three leading AI models — ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini — and asked them to identify which ones are real, then counted it as a point for the respective discipline when a model got it right. (I made sure to use a different Claude account for the Turing test than I did to mock up the abstracts.) This was the exact prompt:

The following are two abstracts for the scholarly article “______” in the journal ______. One is real and one was generated by AI. Without using the web, determine which abstract is real. Explain why you chose this abstract.

In total, grievance studies earned just 1 out of 12 points — i.e., Claude’s abstracts were mistaken for the real ones 11 times — while JCI earned 8 out of 12 points. A majority of the AI models mistakenly identified Claude’s abstract as the real one for every single one of the grievance studies papers, but only one of the JCI papers. Gemini and Claude failed to identify any of the correct abstracts for the grievance studies papers, while Gemini correctly identified every JCI abstract and Claude only missed one. ChatGPT failed three out of four times for both fields.

This is about as clear a result as you can get: The grievance studies abstracts are easier to fake if you know the field’s jargon. Even if the grievance studies affair had serious methodological errors, then, it seems like it identified a real problem. Woke fields are easier to hoax than anti-woke fields, and it’s likely easier to get worthless papers published if they’re left-coded than non-left-coded.

The articles are: “Feminist Geopolitics and the Global-Intimacies of Pandemic Times,” Gender, Place & Culture; “‘Just There for the Fashion, Basically’: Politicized Fem(me)ininity in the Fat-O-Sphere,” Fat Studies; “Jagged Love: Narratives of Romance on Dating Apps during COVID-19,” Sexuality & Culture; and “‘I Think Most of Society Hates Us’: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis of Interviews with Incels,” Sex Roles.

For the journal Fat Studies, I used the second most-cited article, a study of gender expression by body positivity influencers, because the most-cited article is the introduction to a special issue.

I asked it to generate an abstract for the truly controversial JCI articles listed above (e.g., defending use of the N-word), but it refused.

The following are the real abstracts.

GS #1: B

GS #2: B

GS #3: A

GS #4: B

JCI #1: A

JCI #2: A

JCI #3: B

JCI #4: B

This is broadly in line with my impressions. There is real rot here, but Lindsay et al. have somewhat exaggerated the problem.

I appreciate the reminder not to reflexively write off articles with silly-sounding conclusions, and I like the attempt at coming up with an impartial experiment. But I think you're downplaying how bad the Grievance hoax articles are. This is from the dog park one:

> There are many ways to define and conceptualize oppression. In the context of this work, I’ll borrow from Taylor’s definition which has gained considerable traction, ‘What it means to occupy a public space in non-normative ways’ (Taylor 2013)... on Taylor’s definition, raped female dogs were not oppressed because rape was normative at dog parks. This raises interesting and highly problematic issues as to the agency of female dogs in particular spaces as well as with intrinsic victim blaming in female dogs which obviously extends into the analogous circumstance under (human) rape cultures within rape-condoning spaces. Simply put, rape is normative in rape cultures and overtly permissible in rape-condoning spaces, and therefore (human and canine) victims of rape suffer the injustice of not being seen as victimized by so much as complicit in having been sexually assaulted, which can even extend to the feminist researcher herself (cf. De Craene 2017).

To point out just two problems with this passage:

1) Their definition of oppression doesn't seem reasonable in the context that they're using it, and they never try to justify it. Because it is such a narrow definition of oppression, they're able to conclude that raping female dogs is not a form of oppression.

2) The writing just seems obfuscatory. For instance, I cannot figure out what the phrase "which can even extend to the feminist researcher herself" means in this context. Or what the "agency of female dog" thing means.

In contrast, I think the JCI articles (what I've read of them, at least) are way more well-written. They try to address foundational concerns that a reader would have, unlike the dog park article, which never even addresses the fact that dogs have entirely different psychologies than humans and can probably not even conceive of the "injustice of not being seen as victimized by so much as complicit in having been sexually assaulted."