I drove across Wisconsin yesterday. Actually, I didn’t do the driving; I never learned how to drive and I don’t have a license. But it’s poor writing to start off in the passive voice, and in any case, I did in fact make it across the state of Wisconsin.

If you’ve never been to Wisconsin during an election year, you’re not missing out. The vibes aren’t much different than anywhere else in the Upper Midwest, and besides an abundance of billboards advertising cheese (and surprisingly not an abundance of drunk drivers), you wouldn’t know you’re in Wisconsin and not, say, Minnesota or Illinois where people’s votes don’t matter. For all the ungodly amounts of money being poured into the media markets, most people just aren’t obsessed with politics. Every once in a while, you run across some freak with a dozen yard signs, but otherwise the good people of the Badger State have given a curt, polite, passive-aggressive Midwestern middle finger to the vultures of the Trump and Harris campaigns who have flocked in to scavenge among the bodies of the few remaining undecided voters.

This isn’t a travel blog, dear reader, so I’ll spare you the details about attractions, places to eat, and the like. You and I both know you’re here for the horse race. In just over a week, the good people of Wisconsin will once again be deciding The Most Important Election of Our Lifetime™ and with it the Fate of the Republic. I don’t pretend to know how the election is going to end, but here are a few thoughts I had while traveling that aren’t long enough to deserve their own posts.

1. There’s surprisingly little non-broadcast advertising.

I don’t watch television or listen to the radio, and I have location tracking and personalized ads turned off on all my accounts and devices, so I’m not privy to the vast majority of politicking that most people endure on a daily basis. Apparently, there’s a lot of it. The campaigns and super PACs are spending over $500 million on television advertising alone just in the last two months of the election, which is significantly more than any previous year and more than half the amount spent on the campaign in toto over the same period. You’d think that eventually the orgs would reach a point of diminishing returns where a marginal dollar spent online or in broadcasting accomplishes less than a dollar spent in the real world, but apparently we haven’t reached that point yet.

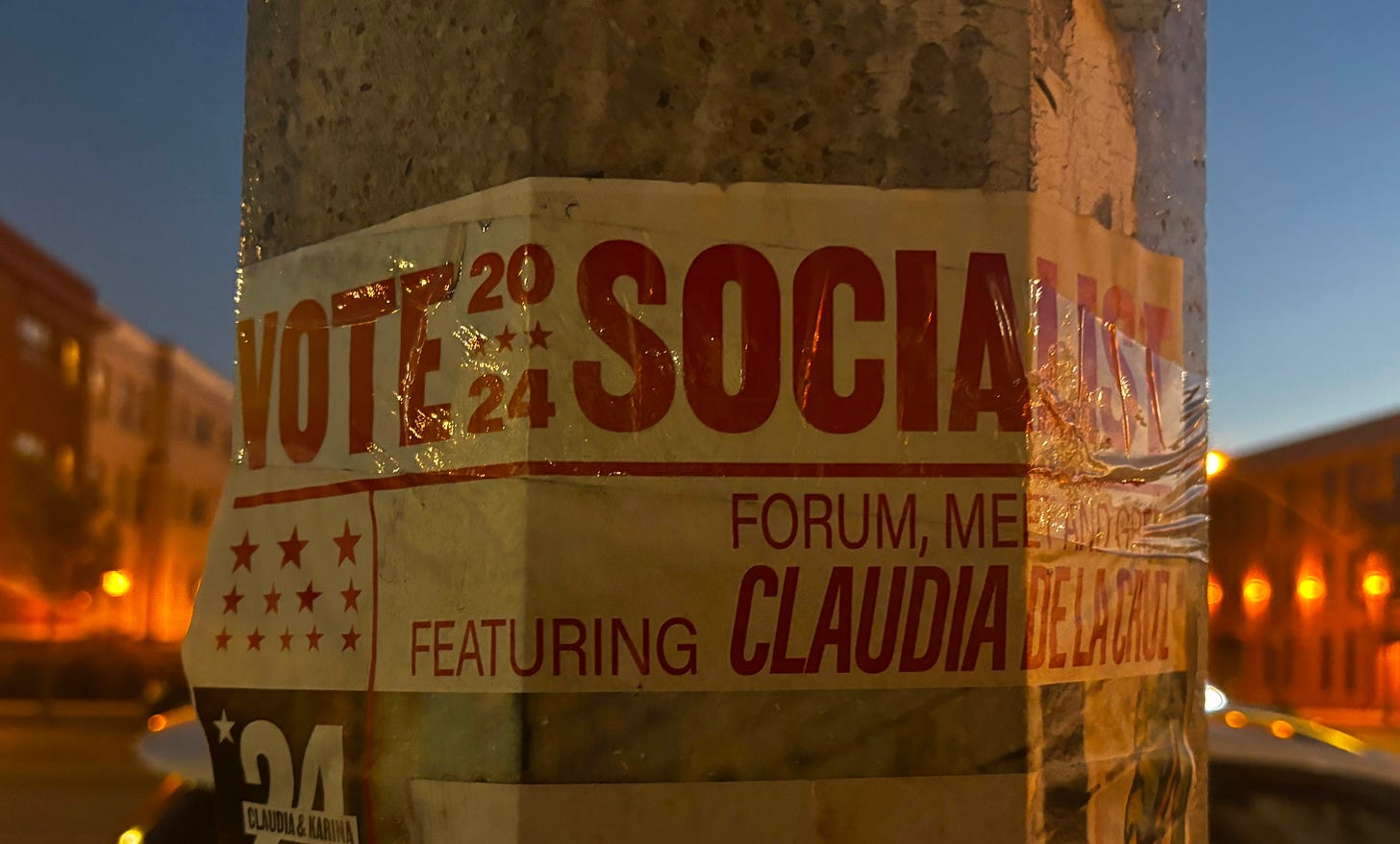

From what I read online, I get the impression that the swing states are being bombarded with high-budget, focus group-tested television ads 24/7. I can’t say if that’s true, but I can say that when you’re only paying attention to the real world, the campaign doesn’t actually look that sophisticated. I spent a few hours in Madison and a full day in Milwaukee, and I never saw a single campaign canvasser or volunteer. There’s an average of maybe one yard sign per block, plus one for every couple of miles in rural areas along the highway. There’s a fair number of Trump and Harris billboards in the cities, but they’re nowhere near the saturation levels you might expect, and they’re vastly outnumbered by a weird, possibly egomaniacal personal injury lawyer who’s also apparently a local celebrity. Besides that, I saw one LED billboard truck for Harris and a free alt magazine with an endorsement of Harris on the cover. In a few neighborhoods, the Trump and Harris campaigns are even out-advertised by posters for the Marxist-Leninist Party for Socialism and Liberation and something called the “Milwaukee League of Anarchists.”

2. Real-world ads are weird, and that’s good for Trump.

Of the little advertising that’s actually done in the real world, almost none of it is paid for by the campaigns and their designated super PACs. The big orgs are all focused on television and digital ads, so they’ve essentially ceded the lower-tier mediums like billboards to the less sophisticated and worse funded elements of their coalitions.

All but a handful of the billboards I saw were paid for by individual people and grassroots groups not affiliated with candidates and parties. One billboard outside Milwaukee, which just features a Trump logo, says at the bottom that it’s paid for by Dan Newlin, a Florida lawyer and Trump superfan who’s funding a multimillion-dollar nationwide campaign to elect the ex-president. Another billboard outside Eau Claire, which just has a Harris-Walz logo next to a reminder of the election date, says at the bottom that it’s paid for by “KH Rodman, Air Force Veteran,” a person with no apparent online presence.

These are some of the less crazy examples. The below billboard in Madison is paid for by a retired realtor who describes herself as “68 years young, the daughter of a communist mother & a Rush Limbaugh loving father who understandably got divorced,” who “spent most of [her] adult years as an un-engaged ‘closet conservative’ in DemocRAT infested Chicago.” (Pardon me if I don’t believe that she is, in fact, a Democrat for Trump.)

I wouldn’t be surprised if this billboard is effective. “ECONOMY” and “BORDER” are Trump-coded words; voters who rank inflation and immigration as their top concerns are the most likely to say they’ll vote Republican. And “Democrats for Trump” is probably a good slogan if you want to peel off Black and Latino voters from Harris, which is a key part of the Republican strategy this year.

But the ad also looks really low brow, like it’s made by someone who’s really into healing crystals and only learned how to use MS Paint a week ago. The closest pro-Harris analogue I could find is this one, which is just across the street.

This one is also graphically unsophisticated, but it has a more detailed message than the Trump sign. Whereas Trump simply “ECONOMY,” Harris supports doing a specific thing about the economy. This is a smart move for Harris—voters already have an opinion about Trump, but they’d like to know what Harris plans to do in office before deciding whether to vote for her—but it also puts her at a disadvantage in the hyper-concise medium of billboard advertising. The low-educated people who are most likely to be swayed by billboards are already a major Trump constituency. And those people can more easily project what they want to read onto an ad that just says ECONOMY and BORDER than they can onto an ad that says if you support X policy on issue Y, then you should vote for candidate Z.

(I also don’t think it’s a stretch to say that many of the people who are open to voting for Trump might resonate with a group called “Concerned Americans for America” whose website looks like a Free Republic thread from twenty years ago.)

3. A effective altruist super PAC captured the Democratic donor class.

I said I don’t watch television, but if I did, I’d probably be seeing a lot of ads made by Future Forward, the Harris campaign’s preferred super PAC, which has reserved at least $350 million in TV spots for the last month of the election. Teddy Schleifer at the New York Times has done some great reporting on FF in the past few weeks, including a feature on its secretive decision-making process, as well as the scoop that it got $50 million in dark money from Bill Gates.

If you were following Schleifer’s reporting in 2020 as well, you would know that FF is deeply influenced by effective altruist principles. The PAC’s biggest funder in 2020 was Facebook co-founder and effective altruist Dustin Moskovitz, who contributed $47 million out of the $151 million it raised that cycle. The second-largest funder was crypto magnate and effective altruist Sam Bankman-Fried, who contributed $10 million. (All of these figures are publicly available on the Federal Election Commission’s website.)

As David Shor told Vox’s Dylan Matthews in 2018, Moskovitz was the first donor he had ever seen who asked how many votes-per-dollar could be generated by different advertising campaigns and canvassing operations. Schleifer wrote shortly thereafter that:

Moskovitz has sought to bring the brainy, data-driven approach that he has pioneered in his philanthropy to his political program in 2020. He has tried to calculate the “cost-per-net-Democratic-vote,” combing through academic literature to mathematically determine where each marginal dollar from him can make the biggest difference.

According to Schleifer, the topline conclusion from Moskovitz and FF’s research was twofold: The most effective political intervention is to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in late television and digital ads, so they’re still fresh in voters’ minds on election day; and it’s necessary to test the effectiveness of these ads in real-world randomized controlled trials, something that had almost never been done in political advertising before. Thus,

Future Forward uses online surveys to measure which potential ads will move voters most. It’s a laborious process, but officials say the ads that emerge are on average 35 percent more effective than those they reject.

(A final point on FF’s effective altruist influence: I don’t know where the name “Future Forward” comes from, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s a nod to longtermism.)

FF’s strategy was phenomenally effective in 2020, and after the election it quickly became the preferred super PAC of the Biden White House and mainstream Democratic donors. In the 2022 cycle, according to leaked tax records, FF received at least $15.2 million from the Open Society Policy Center, which is controlled by top Democratic donor and non-effective altruist George Soros. It also received $7.2 million from longtermists and early Anthropic AI investors James McClave and Emily Berger, as well as another $3.3 million from Moskovitz. Stephen Mandel, a hedge fund manager and Democratic megadonor with no apparent connection to effective altruism, was the top non-dark money donor at $5 million.

In mid-2023, the New York Times reported that Biden’s re-election campaign was designating FF as its primary independent expenditures vehicle, replacing the previous preferred super PAC, Priorities USA Action. The Times quotes Biden advisor (and now FF senior advisor) Anita Dunn:

“In 2020, when [FF] really appeared from nowhere and started placing advertising, the Biden campaign was impressed by the effectiveness of the ads and the overall rigorous testing that had clearly gone into the entire project.” […] The group, she added, had “really earned its place as the pre-eminent super PAC supporting the Biden-Harris agenda and 2024 efforts.”

Before he dropped out of the race, Biden also lent his 2020 campaign’s finance director and several of his senior advisors to support FF’s fundraising and Latino outreach operations, while top Democratic donors took Biden’s cue and began redirecting their giving to FF. Donors so far this cycle include former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg ($19 million), LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman ($10 million), the late hedge fund manager James Simons and his wife Marilyn Simons ($9.6 million), newspaper magnate Fred Eychaner ($7 million), DreamWorks co-founder Jeffrey Katzenberg ($2 million), Family Guy creator Seth MacFarlane ($1.5 million), Netflix co-founder Reed Hastings ($1 million), and former Facebook executive Sheryl Sandberg and her husband Thomas Bernthal ($1 million).

Similar to effective altruist interventions in philanthropy, FF has faced criticism from less prominent and less efficient Democratic PACs and organizers for ignoring more traditional campaign tactics like mailers and ground operations, while accruing undue influence with the White House. As Schleifer reported earlier this year, Biden met one-on-one with Moskovitz in February ostensibly to discuss AI safety—but, according to Schleifer, “the subtext was obvious: Wouldn’t it be great if Moskovitz and [his wife Cari] Tuna could fork over […] cash again?”

4. Politics has nationalized.

This is the shortest observation so far because it’s obvious and unoriginal, but it’s still very important. I didn’t count every yard sign that I saw, but I’d bet there were no more than one-third as many signs for Tammy Baldwin and Eric Hovde, the Senate candidates in Wisconsin, as there were for Harris-Walz and Trump-Vance. And there were probably no more than one-tenth as many yard signs for state legislative candidates as there were for Baldwin and Hovde. That’s not surprising, since our media environment is so nationalized. But it does mean that important local issues may be getting short shrift, while candidate quality may increasingly be taking a back seat to culture war drama. Hovde, the Wisconsin Republican Senate candidate, is a banker who lives in California and recently said he knows nothing about the farm bill. Earlier this year, after speaking on a radio show about how the 2020 election was rigged because of nursing home voting, he had to clarify that he doesn’t think elderly people should be deprived of the right to vote.

5. Trump is probably going to win.

I’ll be registering all my predictions closer to election day, from (the very important) Denver Initiated Ordinance 309 on up to the presidency. Today, I’ll give you a sneak peek: I think Trump is going to win all seven swing states, and I think he’ll probably win the popular vote. The pundits almost universally have the race as a toss-up, but I’m with the prediction markets that it’s more like 66-33 for Trump. I’m a believer in putting your money where your mouth is, so I have a slightly larger than trivial amount of money bet against Harris on PredictIt, where her numbers are the highest. Here’s why:

At this point in 2016, Hillary Clinton was polling 5.4 points ahead of Trump. On election day, she was polling 3.2 points ahead of Trump. She won the popular vote by 2.1 points and lost the election by 77,744 votes in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

At this point in 2020, Joe Biden was polling 7.8 points ahead of Trump. On election day, he was polling 7.2 points ahead of Trump. He won the popular vote by 4.5 points and won the election by 42,918 votes in Georgia, Arizona, and Wisconsin.

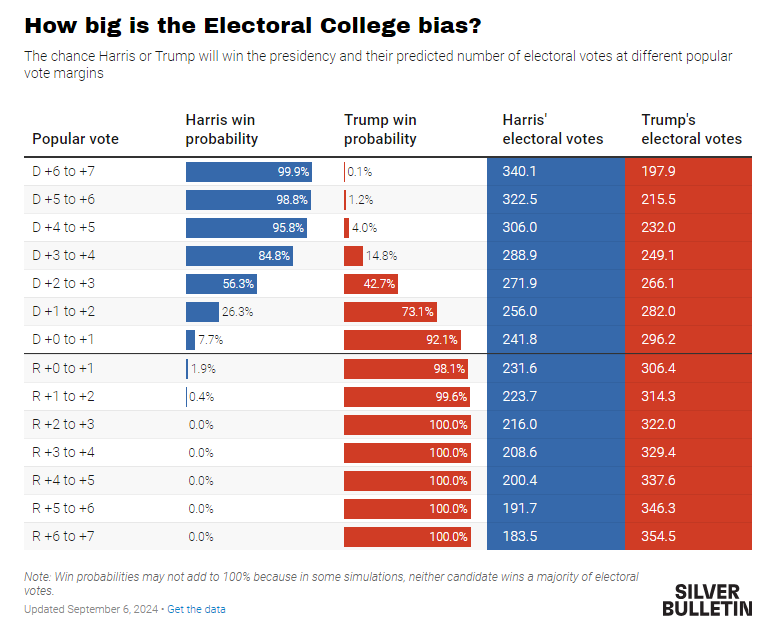

Today, Kamala Harris is polling 0.1 points behind Trump. She may be further behind him according to Democratic internals. Momentum in recent weeks has been against Harris, and Harris needs to win the popular vote by at least 3 points to be the odds-on favorite to win the electoral college.

Some very smart people say we shouldn’t necessarily expect there to be a polling error against Trump like there was the last two times. (One of these smart people is a Substack mutual of mine,

, who’s a political scientist who writes about these things. You should subscribe to him.)I don’t know how confident we can be about this, since we don’t know for sure why the polls got it wrong the last two times, but I’ll take the smart people at their word. Let’s assign a one-third probability each to: (1) a polling error against Trump, (2) a polling error against Harris, and (3) the polls being accurate. If the polls are tied right now, and anything less than a national result of Harris +2 goes to Trump, then the only way Harris wins is if there’s a significant polling error against her. Hence my (poorly informed) priors tell me it’s two-to-one for Trump.

If you think I’m wrong, tell me. Maybe you’ll save me a few bucks on PredictIt!

6. Harris blew it.

No matter who ends up winning, what’s clear is that Harris has run a very suboptimal campaign. Nate Silver pointed this out a few days ago, when he wrote that Harris’s plan to coast off vibes, likability, and coconut trees and brat memes isn’t going to cut it. People already know that she’s a better natured and more moral person than Trump. But they don’t know what she’s going to do about prices, the border, and the economy, which they consider far more important.

From day one, Harris has failed to address these issues in anything approaching sufficient depth. Her campaign website’s issues page has been a running joke for how vacuous it is, and even though she’s managed to put some detailed policy plans to paper over the past month or so, it still seems like she’s more interested in running around and chattering about her biography and democracy and whatnot—the things that Biden talked about, which voters keep saying they don’t care about—instead of talking about what she’s actually going to do if she becomes president.

It didn’t have to be this way. Starting three months ago, Harris could have paired her tough talk about her background as a prosecutor with some genuinely popular policy proposals. Would it really have hurt her to come out for the public option on health care—something that both Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton supported? Ditto for tuition-free college for people making less than six figures. (I think the latter is a terrible policy, but it would have been better for her than what she’s running on now.) Would she really have acquired a reputation as a radical leftist if she allowed a Palestinian American to speak at the DNC for a measly three minutes? I doubt it, but it would have gone a long way to mend ties with the Uncommitted Movement.

I saw a billboard outside Milwaukee that says: “Kamala Harris supports raising the minimum wage.” Okay, that’s a popular position. How high does she want to raise it? No one had an answer to that question until she finally deigned to utter a number on Tuesday, just two weeks before election day and weeks after the first mail-in ballots had been sent out.

Lack of substance has been a major problem for Harris throughout the campaign, and to her credit she’s occasionally nodded to her policies to assuage voters’ uncertainties about her. But heading into the final stretch, she’s not even pretending to address voters’ main concerns.

On Monday, a few days before I passed through Wisconsin, Harris was stumping in a Milwaukee suburb with Liz Cheney, who’s apparently the campaign’s top surrogate in the election’s closing weeks. The campaign says they want to give anti-Trump Republicans “permission” to vote for Harris. And maybe it’ll work. But how many people could there possibly be in Wisconsin who care about Liz Cheney’s endorsement, who would have voted for Trump or stayed home, who are now going to vote for Harris instead? Is it more or less than the number of people who want to know what Harris’s health care plan is? Is it more or less than the number of antiwar progressives and Arab and Muslim Americans who didn’t trust Harris before and now trust her even less precisely because she’s touting her support from the Cheneys?

7. What, me worry?

It may sound like I’m worked up about this, but I’m really apathetic about the whole election. As a rule, I try not to worry about something unless it fulfills two criteria: it’s important—that is, it can reasonably be expected to have an impact on people’s wellbeing—and I can do something about it. “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,” and so on.

An example of something I worry about is how my actions affect the people immediately around me. This is why I make an effort not to shove grandmas down staircases. Some examples of things I don’t worry about are whether there’s a teapot orbiting the sun between Earth and Mars (trivial), how I’m going to prevent the Titanic from sinking (intractable), and how I’m going to stop Trump from winning the election (also intractable). If Trump is going to win, I’m not going to be the one to stop him, no matter how hard I vote for Harris or how much money I give to math nerds who run a super PAC. So why should I expend any bandwidth on it, especially when I can do more impactful things with my time instead?

In a classic blog post, Scott Alexander asks why some people privilege politics above other means of improving the world. “Being a perfect person,” he says, “doesn’t just mean participating in every hashtag campaign [and voting, donating to political campaigns, etc.] […] It means spending all your time at soup kitchens, becoming vegan, donating everything you have to charity, calling your grandmother up every week, and marrying Third World refugees who need visas rather than your one true love.” Some of these things—namely, politics—are a lot less effective than others and deserve a lot less of your attention.

In my experience, the people who obsess over politics to the exclusion of other more important things tend to be both ineffective at changing the world and very poorly adjusted and neurotic. (See the comment section of my post on Tiedrich for some examples.) If there’s one thing you should strive for, it’s to be the opposite of these people. Touch grass. If you live in a swing state, you should vote (see below), and if you really care, you can donate to local races. But otherwise, the election just isn’t going to be influenced in any meaningful way by anything you do, and there are much more important things you can do instead if you want to execute your perceived civic duties.

8. Voting is gay (pejorative).

The above reason is partly why I’m very prejudiced against voting. I used to be dead-set against voting, not merely prejudiced, because I thought the chance of anyone’s vote influencing an election outcome is infinitesimal. But after reading some numerically literate analyses, I accept that it’s rational to vote in a swing state. If the value of a favorable election outcome is as little as $100 billion, and you have a 1-in-2 million chance of changing the election outcome as a swing state voter, then your vote is worth at least $50,000 (assuming you’re perfectly altruistic), which is far greater than the cost of voting.

Still, I don’t vote. There are three reasons for this.

First, I don’t live in a swing state, so my chance of affecting the election outcome is far lower than 1-in-2 million. Second, like Bryan Caplan, I think politicians are bad people and I don’t want anything to do with them. If you wanted me to vote, you’d probably have to pay me a few hundred dollars for the first time—my voting virginity is very important to me—and at least a hundred dollars every time thereafter. I assume this is far greater than the average voter.

Finally, I think it’s basically impossible to tell ex ante which electoral outcome is going to be better for the world, all things considered. I’ve written before that I think Harris would be a better president than Trump on almost all of the most important issues, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it would be better if Harris won the election, since her victory could negatively affect the political landscape in unpredictable ways.

If you want some concrete examples to better understand what this means, consider the following: From an ex ante perspective, I would have supported every Democratic candidate in the past six presidential elections, since and including 2000. But there’s a very good case that it would have been better if half of those elections were won by Republicans. If Al Gore had won in 2000, he wouldn’t have launched PEPFAR and saved 25 million lives. If Mitt Romney had won in 2012, he probably would have stopped Trump from becoming a serious political figure. And if Trump had won in 2020, he wouldn’t have been radicalized by losing the election, tried to figure out how to staff his second administration with competent yes men, and become the favorite to win the election this year.

We ought to take concerns like this seriously. You can imagine, say, that if Harris wins, the Democrats don’t learn their lesson about running on coconut trees and brat memes, and we end up with President Logan Paul from 2029 to 2037. That’s hyperbolic, but you get the point. If my presidential election track record is no better than a coin toss, I should probably just stay home.

9. Still ridin’ with Biden.

If I did end up voting, I’d write in Joe Biden. I don’t like the man, and I think he should be thrown into a volcano along with everyone else who voted for the Iraq War. But writing in Biden strikes me as the funniest possible thing to do.

If I was into third-party voting, I could see the case for supporting Jill Stein as a middle finger to the vacuity and obsequiousness to Israel of the Harris campaign. And (again, if I was into voting at all) I’d like to reward the Libertarian Party for nominating a functioning adult this year instead of following the incoherent paleo strategy and choosing a candidate who just talks about transgender children all the time.

I asked ChatGPT for some other names I could write in, and its suggestions were all really lame, like Mickey Mouse. When I prompted it for some more edgy and obscure options, it gave me an okay list that includes Satoshi Nakamoto, Aleister Crowley, and Slavoj Žižek. One option that I thought of, which is very funny to me for reasons that elude me, is Muqtada al-Sadr. Claude and Gemini both told me they’re not allowed to give election-related advice.

10. The election will be stolen fair and square.

If you’ve made it this far, I think you deserve to hear my most controversial opinion to date: I think any sufficiently close election is stolen. This includes 2000, 2004, 2016, and 2020. And if the polls are right this time, it’s going to include 2024.

When I say an election is stolen, I don’t mean that the number of votes counted for each candidate doesn’t reflect the number of ballots cast by eligible voters. China, Venezuela, and Italy didn’t rig the outcome in 2020; dead people and illegal immigrants don’t vote in outcome-decisive numbers; and Russia didn’t change vote tallies in 2016. But the margins in each of those contests were so close that they were more than made up by unfair yet legal practices and dirty tricks by the winning side. I think it’s fair to say the 2020 election was “stolen,” in the sense that the outcome was decided by untoward behavior on behalf of Biden, because intelligence agency officials lied that the Hunter Biden laptop was Russian disinformation; social media companies deliberately suppressed the story; and the media had spent five years covering Trump uncharitably and making up fantastical spy stories about Russian collusion. Similarly, I think it’s fair to say the 2016 election was “stolen” because the DNC’s emails were illegally hacked and leaked; Republican states suppressed minority voters; the media was obsessed with Hillary Clinton’s emails; and James Comey inappropriately reopened the email investigation days before the election. And I think if Clinton had won in 2016 or Trump had won in 2020, you could have made an equally valid argument that either of them had also stolen the election.

I don’t think using the term “steal” in this way robs it of meaning or descriptive value. We commonly refer to things as having been stolen if they were acquired by duplicitous means even if everything that happened was technically above board. A runner can steal a base in baseball. A poker player can “steal the pot.” A breakout star can “steal the show” or “steal someone’s thunder.” Go back and read the first sentence of this paragraph. Is the term “rob” suddenly meaningless because I used it to refer to something other than taking someone’s property from them through the use of force?

If you haven’t caught on by now, I’m not some sort of election denier or January 6th-er. The point of saying an election is “stolen,” in the sense I use the term above, is to point out the corruption that’s both legal and endemic to the American political system. If Trump wins this year, we’ll have a president who stole the election by engaging in blatant quid pro quo with billionaire donors and shadily helping left-wing third parties in swing states. If Harris wins, we’ll have a president who stole the election by accepting hundreds of millions of dollars in billionaire dark money and using dirty tricks to try to keep third parties off the ballot.

And either of them will have stolen the election fair and square.

Nah, fuck you you fucking fuck

Get a license, bum